1500 Word Critical Reflection

Introduction

I run a dialogue-based lifelong learning programme promoting self-development and social engagement in Japan. Over 200 people have participated in the programme for the past three years. The alumni and I have spent time sharing sensitive things, such as personal trauma, during the programme and have developed a solid relationship where we can discuss any topic without hesitation. Through this educational intervention, I tried to enhance the relationship between these alumni (Japanese adults) and the Palestinians, who are suffering from the ongoing war. I expected the people involved to raise their political voices, change awareness toward the Palestinians, and start to take action after the intervention.

The reason to interfere is mainly based on two points. The first is the Japanese people’s avoidance of politics. According to the survey conducted by the Japanese Cabinet (2018), the percentage of Japanese youth who said they were interested in politics was 43.5%, the lowest of all participating countries. Another research suggested its background as apathy and fear of harming others (Okamoto, 2004). Toyama et al. (2022) pointed out that this restraint may reduce the quality and degree of citizens’ voices reflected in policy. However, in other words, encouraging citizens to raise their voices and participate actively in political activities can improve policy. The second reason for the intervention is the possibility of sharing realities to move the public, inspired by Osman’s (2017) article. Just as how black people suffered terrible discrimination was spread all over the world through videos, which led to the huge movement of “Black Lives Matter”, I thought sharing the realities of how citizens are suffering in Palestine would have also had an impact on the awareness of Japanese people.

Intervention Design

In this intervention, it was evaluated as an enhancement in the relationship if the awareness or behaviour towards Palestinians changed between before and after the intervention. In addition to sharing the realities, the design was focused on “listening” which could invoke people’s self-confidence to take action, inspired by Murdoch et al.’s (2020) article. Furthermore, other psychological theories were utilised to enhance the relationship.

Outline

Intervention method: 90-minute online session (date of implementation: 6/12/2023 8:00 pm – 9:30 pm JST)

Target group: graduates of the lifelong learning programme in Japan

Number of participants: 6

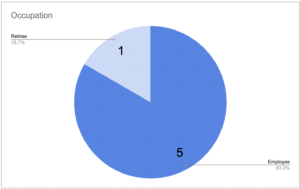

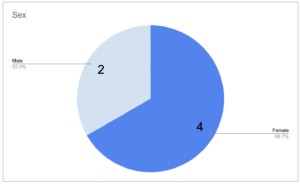

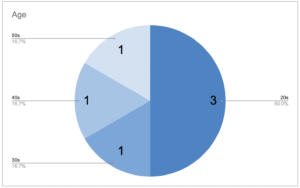

Characteristics of participants:

To ensure the effectiveness, two considerations were taken into account in the initial setting. The first was to narrow down the range of participating graduates. The number of participants was limited to ensure that each individual had enough time to speak up and create a situation where they felt listened to. Also, only the participants who had attended the programme at the same time were invited. Given the cultural context in which it is difficult to talk about politics, I thought the group which had higher ‘psychological safety’ (Edmondson, 1999), a shared belief in being more secure against interpersonal risk-taking, was ideal. Second was to keep the level of ‘listening’ and ‘psychological safety’ as high as possible. I asked participants to concentrate on listening, refrain from speaking while the others were talking, and be considerate when interrupting. In addition, I recomended them to reserve judgment of right or not during the session to create tolerance for failure, which is said to increase psychological safety.

Assessment

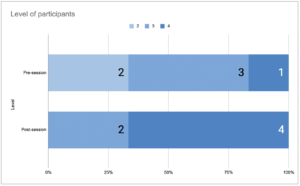

The relationship status was labelled 1-5 in order to ascertain whether the relationship had increased before and after the session beforehand. Participants were asked to answer which level they were in before and after the session and the background of their status.

1: Not interested in

2: Interested in but not doing anything

3: Interested in and take action just by themselves

4: Interested in and take action with close people, such as family and friends

5: Interested in and engage in activities with an unspecified number of people, such as taking a part in protests, spreading information on social media

Session content

6. Sharing thoughts and future actions from participants

The time for participants to speak up was most prioritised over the session. Although attendees were close with each other, I prepared the ice-break time for them to speak up equally to reestablish psychological safety (Edmondson, 1999) because some of them had not talked with recently. Even in the section on input, I provided them with chances to raise their voices by adopting a quiz format. Referring to Osman’s paper (2017), it was also designed to give an impact on participants by sharing realities that everyone would have gotten emotional and found awful, such as young children being badly injured or murdered. I then took the time to ask them to share their thoughts and questions about Palestine that came to their mind, before suggesting actions aligning with the assessment level of 3-5. Based on self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000), I did not force them to choose or implement actions but encouraged them to tell me what they really wanted to do, allowing them to decide not to address it.

Implementation

*The numbers on the graph are the number of people

Here are comments from the participants;

Pre-session

Level 2

“I am interested in what happens to Palestinians but procrastinated to gather information” (2 comments)

Level 3

“I’ve gotten interested in it and attended the talk show about Palestinians” (2 comment)

Level 4

“Sometimes I have a discussion and think about what to do with my friends.”

Post-session

Level 3

“I realised that there is information that I cannot get only from Japanese news, so I will try to go and see news from other countries and get information from various perspectives.” (2 comments)

Level 4

Discussion and possible future research

Analysis of the contribution level of each factor

Change the context

The context was limited in this case to graduates of one specific lifelong learning programme, so the results would change when conducted in other contexts, even they are still Japanese. In the current intervention, 75% (3/4) of those who reached level 4 were in their 20s, whereas the stage of person in his 50s did not change at level 3. I hypothesise that age would have an impact on the relationship and xx said the age and the avoidance of politics had the positive correlation. It may also be possible to analyse to which cultural contexts are more or less effective, comparing to contexts in other countries.

Change in survey methodology

Conclusion

Although this intervention was conducted in a limited setting, it can be said to have succeeded in enhancing the relationship because approximately 70% people increased the level of relationship and reached to the level 4. I believe it contributed to mitigating the avoidance of politics, leading to better policy in Japan. Furthermore, if this session setting were replaced by a school classroom setting, it would be a good example that teachers could promote the educational result of students not only teaching but also listening.

The photo of the header: Taken by Ahmed Abu Hameeda (Unsplash)

Reference:

Japanese Cabinet. (2018). [Survey on the attitudes of young people in Japan and other 6 countries] Wagakuni to shogaikoku no wakamono no ishiki ni taisuru chosa (in Japanese). Ssjda.iss.u-Tokyo.ac.jp. https://ssjda.iss.u-tokyo.ac.jp/Direct/gaiyo.php?lang=jpn&eid=1302. P.18.

Okamoto, H. (2004). [Why do we avoid talking about politics?] Seiji no hanashi wa tabu nanoka? (in Japanese). Www.crs.or.jp. https://www.crs.or.jp/backno/old/No557/5571.htm

Toyama, K., Kawabata, Y., & Fujii, S. (2022). [Psychological research on Japanese people’s avoidance of political participations] Nihonjin no sekkyokutekiseijssanka wo kihisuru shinritekikeikou ni kansuru kenkyu (in Japanese). 土木学会論文集D3(土木計画学), 77(5), I_213–I_223. https://doi.org/10.2208/jscejipm.77.5_I_213

Osman, W. (2017). 15. Jamming the Simulacrum. Culture Jamming, 348–364. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479850815.003.0020

Murdoch, D., English, A. R., Hintz, A., & Tyson, K. (2020). Feeling Heard : Inclusive Education, Transformative Learning, and Productive Struggle. Educational Theory, 70(5), 653–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12449

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Psycnet.apa.org. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2000-13324-007

Japan News Network. (2023, November 7). [Gaza is a “graveyard” for children] Gaza wa kodomotachi no hakaba(in Japanese). Www.youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q8Q_1ZHFpYk

Campos, R., & Martins, J. (2023). Political socialisation narratives of young activists. Contexts, settings, and actors. Journal of Youth Studies, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2023.2224742

Yamada, M. (2016). [Political participation and democracy] Seijisanka to minshu syugi (in Japanese). In www.utp.or.jp. University of Tokyo Press. https://www.utp.or.jp/book/b307141.html