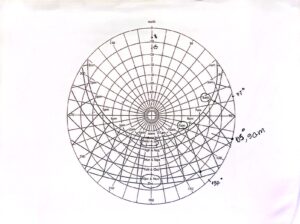

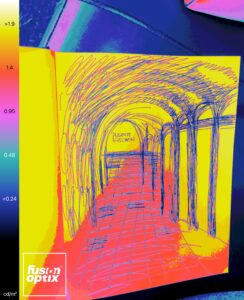

Lighting exercise- sun dial, latitude

Last Friday we did a series of really interesting exercises, such as using a ”sun dial” to figure out what the shadow of the object we were given, or the box that we created, would look like at a specific time of day in a certain season. The sheets we were given are a great tool, as I will use them in the future to figure out where is the best place to position certain elements within a plan or a model, according to the daylight.

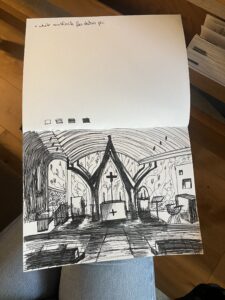

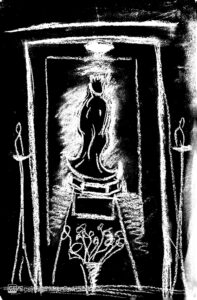

This exercise reminded me of one case study that I thoroughly enjoyed last year in my Architectural History class.: the Vitra Campus Conference Pavilion in Weil am Rhein, Germany, designed by renowned Japanese architect Tadao Ando. Completed in 1993, this minimalist pavilion exemplifies the integration of daylight as a central design element. Ando strategically employs natural light to create a serene and contemplative atmosphere within the space. The pavilion features large expanses of glass and strategically placed skylights, allowing ample daylight to penetrate the interior. The architect pays careful attention to the play of light and shadow, using simple geometric forms and concrete surfaces to enhance the visual experience. The design not only prioritizes the aesthetic qualities of daylight but also addresses its functional aspects, ensuring a well-lit and comfortable environment for various activities. This architectural precedent underscores the significance of daylight not just as an illuminating factor but as a design element that profoundly influences the spatial qualities and user experience within a building. Daylight holds profound significance in Japanese architecture, reflecting a cultural and aesthetic appreciation for the interplay between nature and the built environment. In traditional Japanese architecture, light is not merely a functional element but a design principle that seeks harmony with the surrounding landscape. Modern Japanese architects, such as Tadao Ando , continue to emphasize the importance of daylight in their designs, employing innovative strategies to maximize natural light while maintaining a sense of balance and tranquillity.

While specific practices may vary, a general approach is to have the main living spaces face south, taking advantage of the path of the sun. This orientation takes advantage of the sun’s path in the northern hemisphere, where Japan is located. On the other hand, east-facing windows capture the morning sun, offering a gentle and invigorating light, while west-facing windows receive afternoon sunlight, which can be warmer and more intense. North-facing windows generally receive indirect and softer light, making them suitable for spaces where consistent brightness is desired without the direct glare of the sun.

Thus, the lighting exercise that we did in class is incredibly applicable in real life and it will be a step I will incorporate in all my future models.

Sources: Fig1- Vitra Pavilion- www.vitra.com

Photos taken during class- taken by me (Daria)

Nussaume, Yann. (2009) Tadao Ando / Yann Nussaume. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Patfield, E. W. C. (2017) Kintsukuroi : natural lighting, tectonics and materiality.

Kite, S. (2017) Shadow-makers : a cultural history of shadows in architecture / Stephen Kite. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.