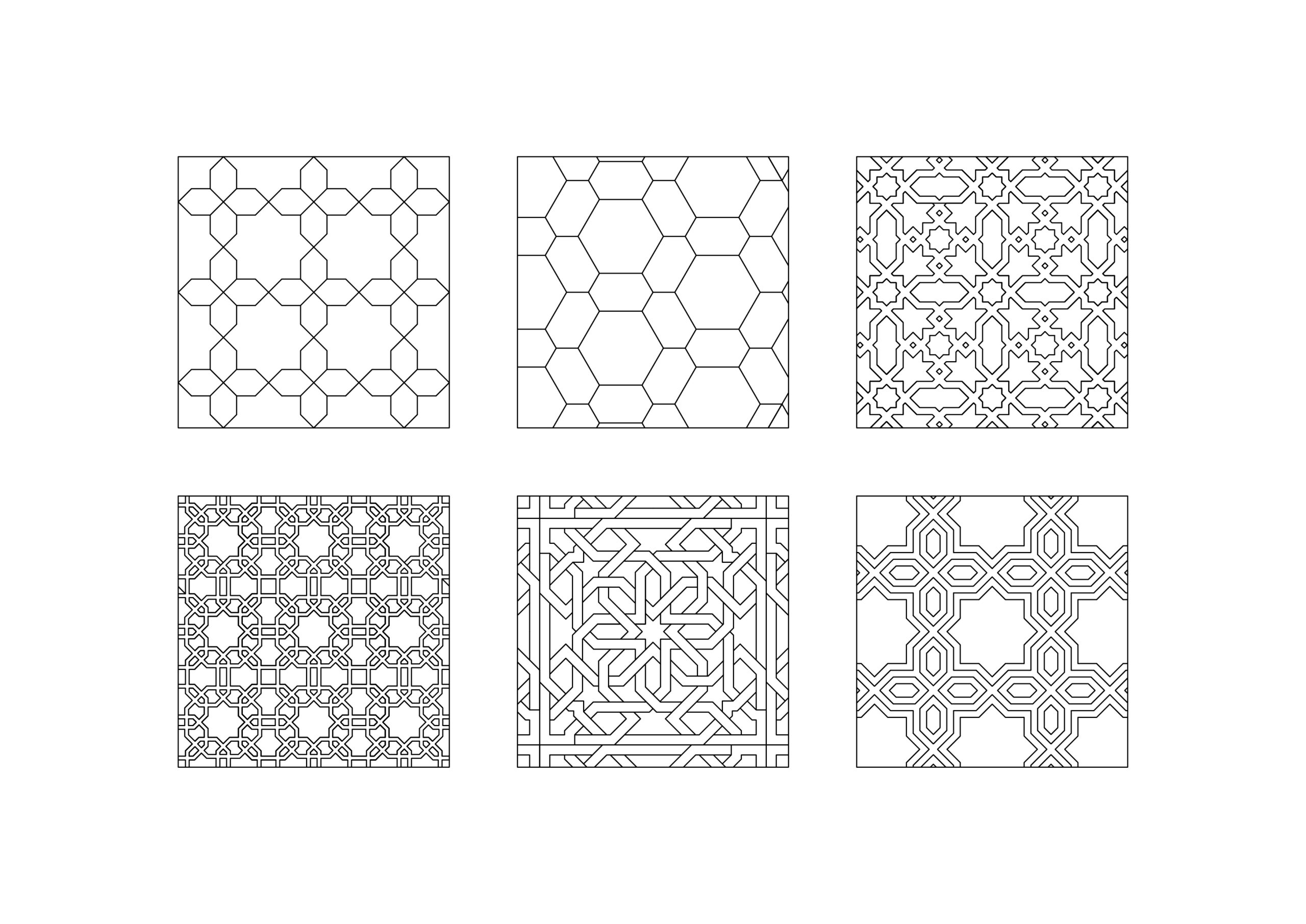

ISLAMIC GEOMETRIC PATTERNS – STUDIES

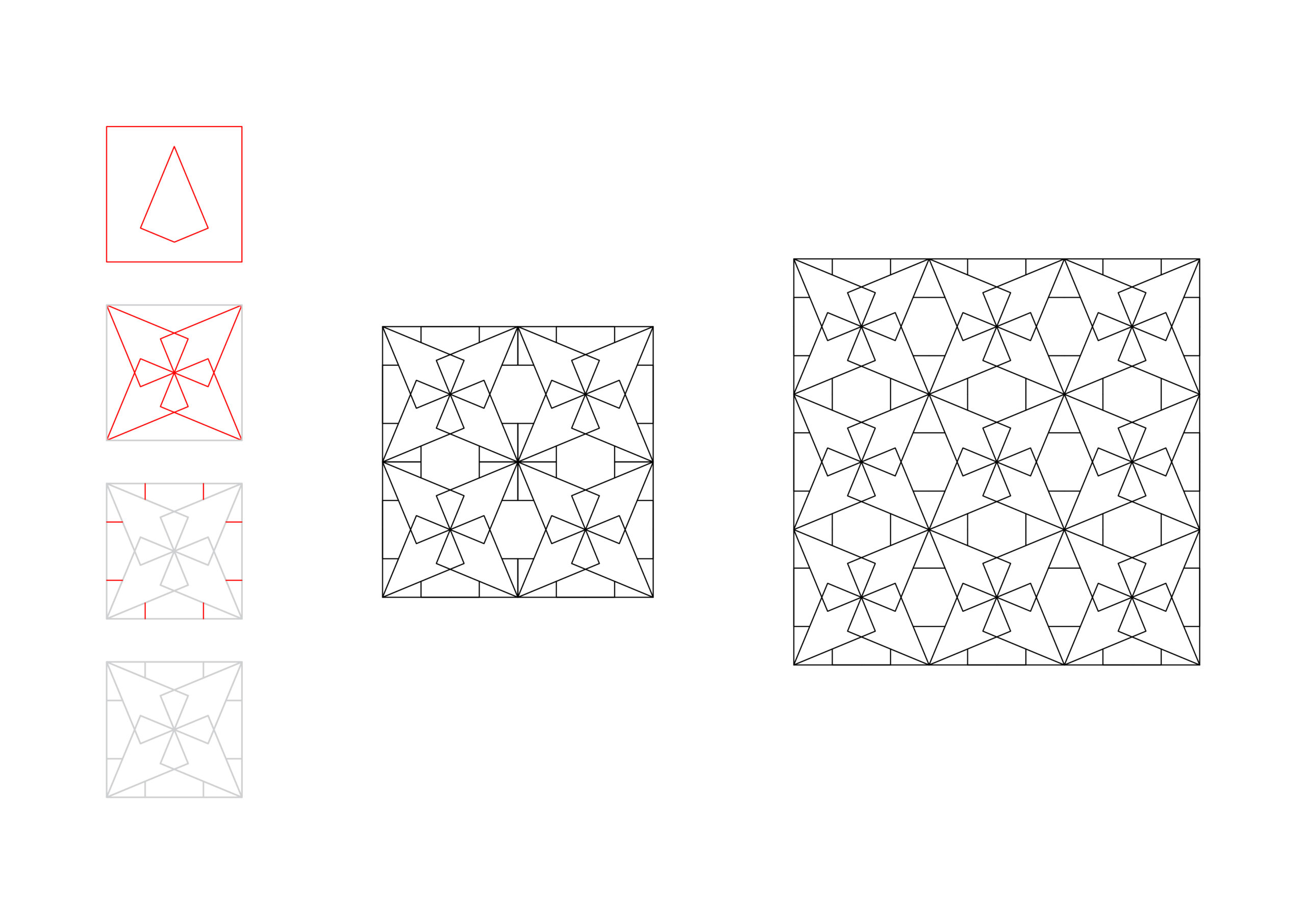

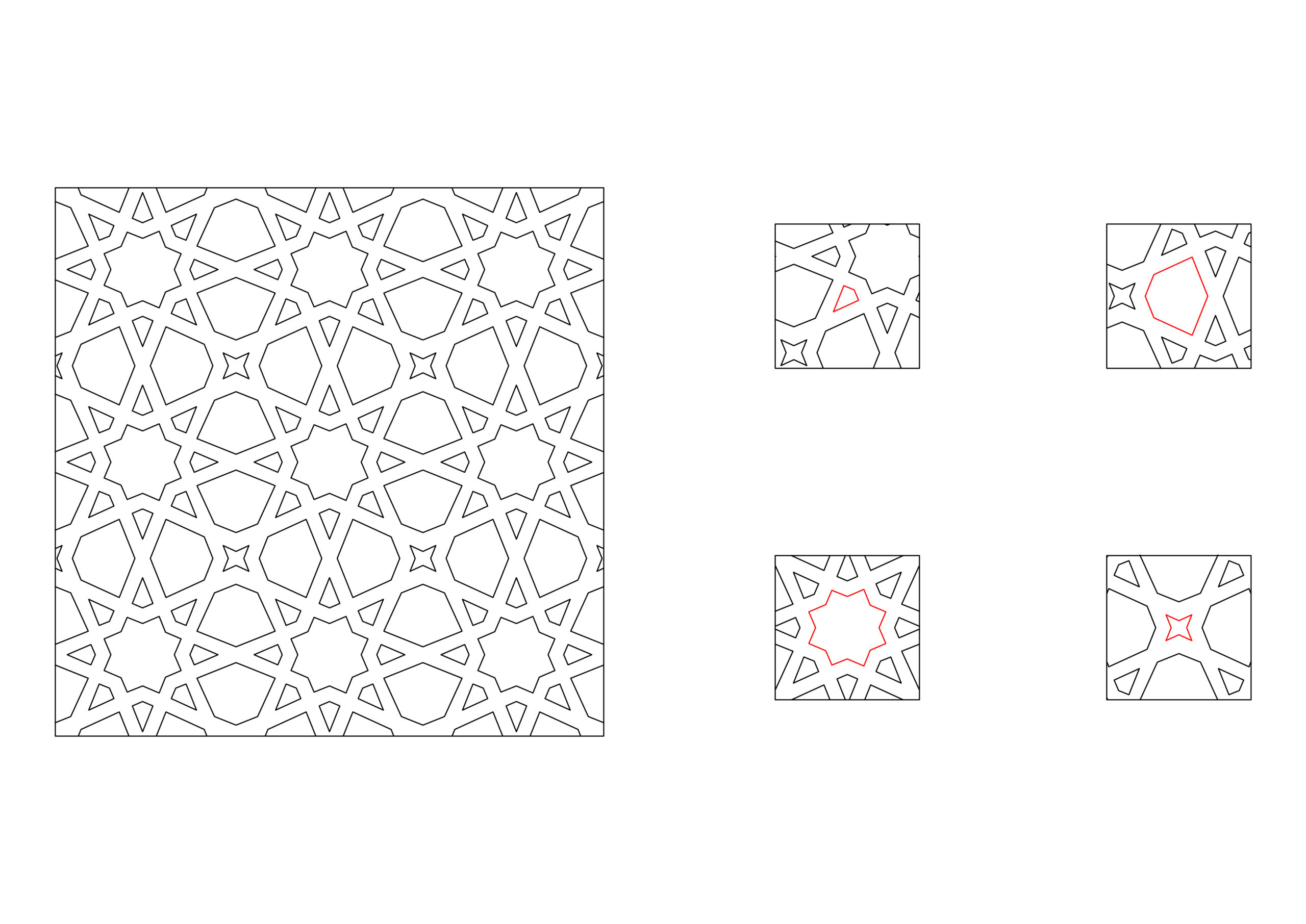

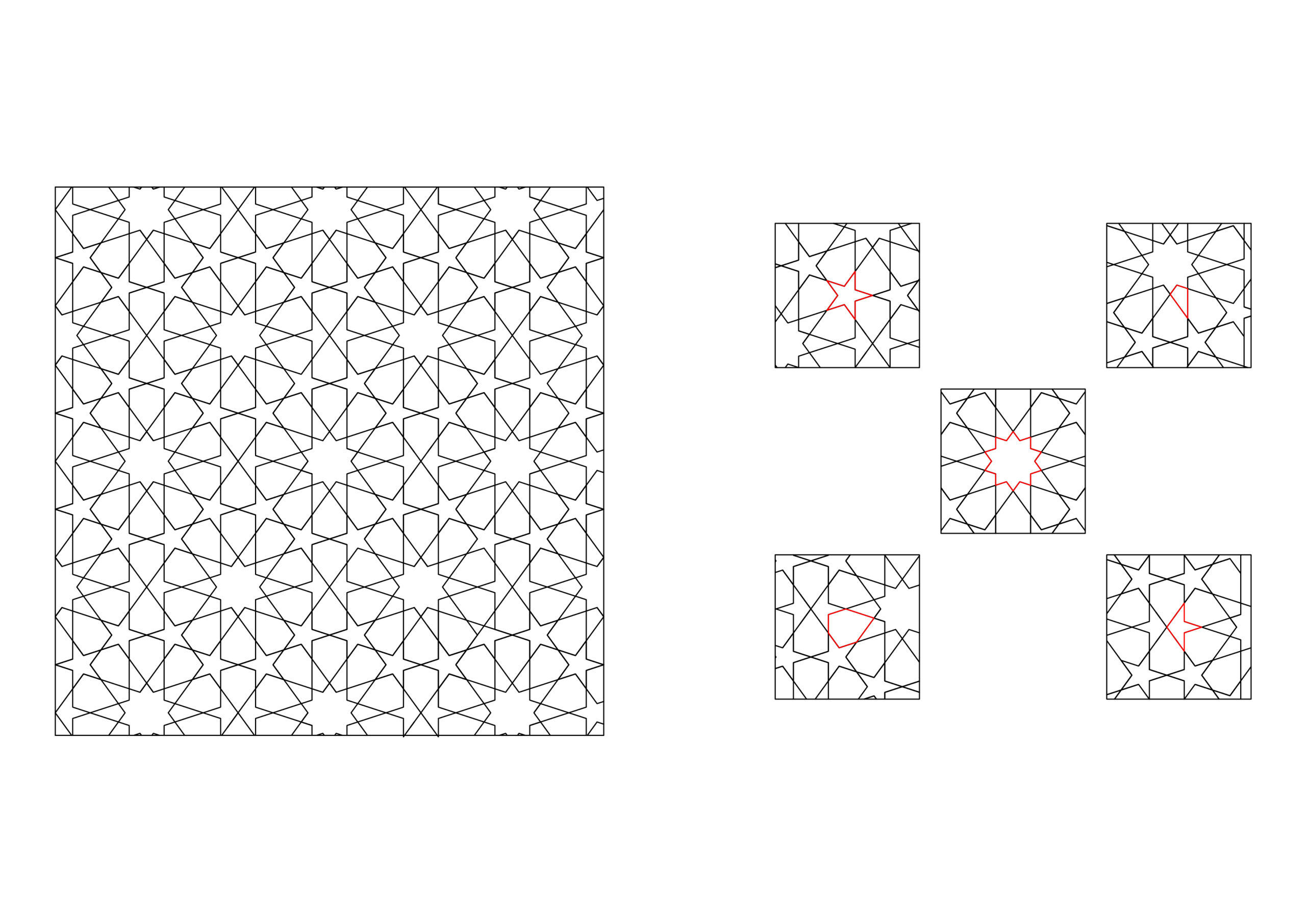

For this project, I did a lot of work on the side exploring different patterns. Each of these stand on their own and have helped me in understanding the construction of Islamic geometric patterns. In this section, which I have entitled studies, I have included a range of these. The first part includes simple line-drawn patterns. The second and third include construction lines as well as finalised and coloured forms. Finally the fourth includes its finalised form in addition to what it would look like when multiplied and continued.

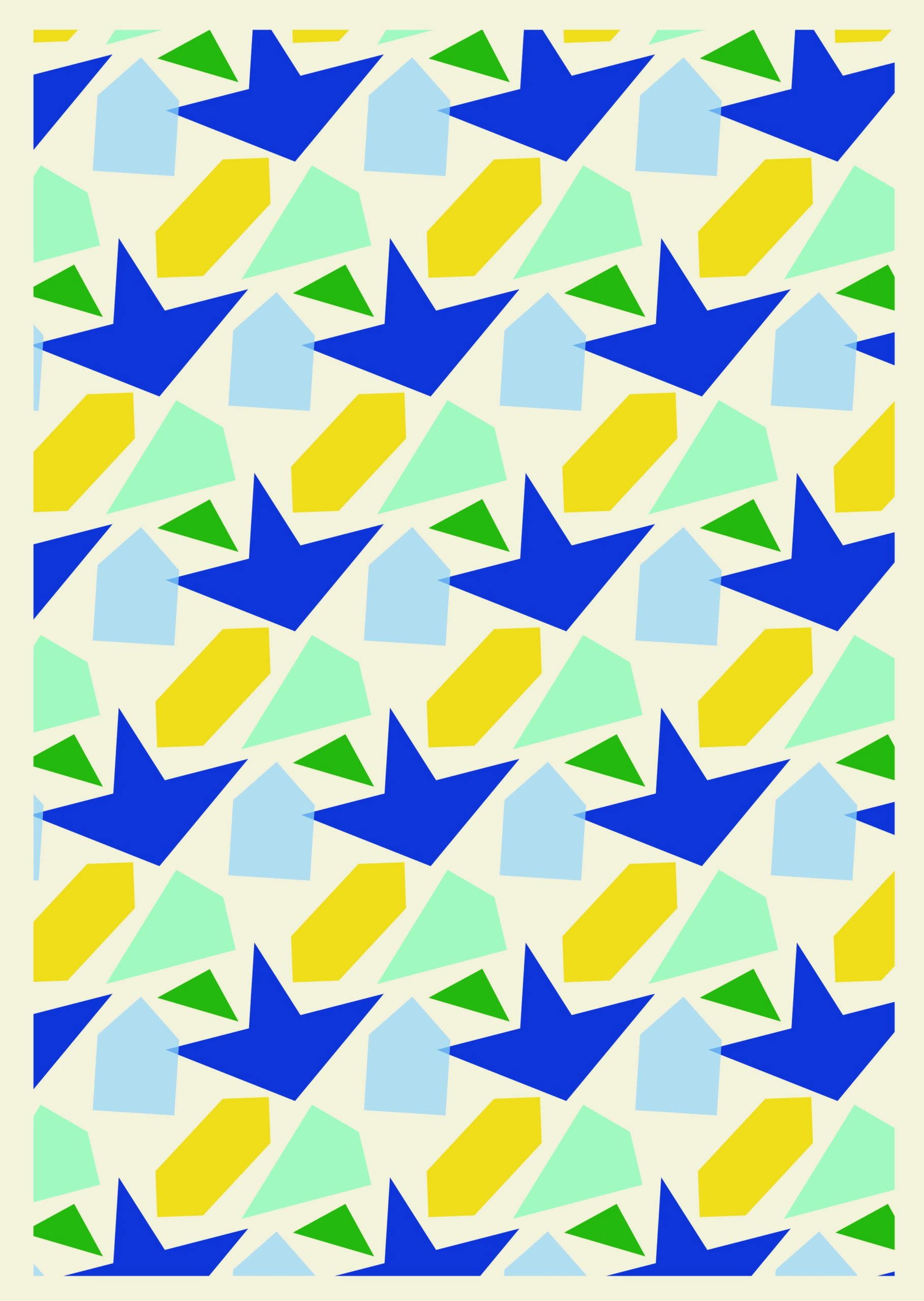

ISLAMIC GEOMETRIC PATTERNS – CHAOS PT.4

Here I’ve mimicked the last sub-project, using another shape extracted from an Islamic geometric pattern, used to make a new one. This one, however, shares more similarities with its inspiration, particularly with respect to its level of detail. Nevertheless, its form strays from the traditional Islamic geometric pattern format.

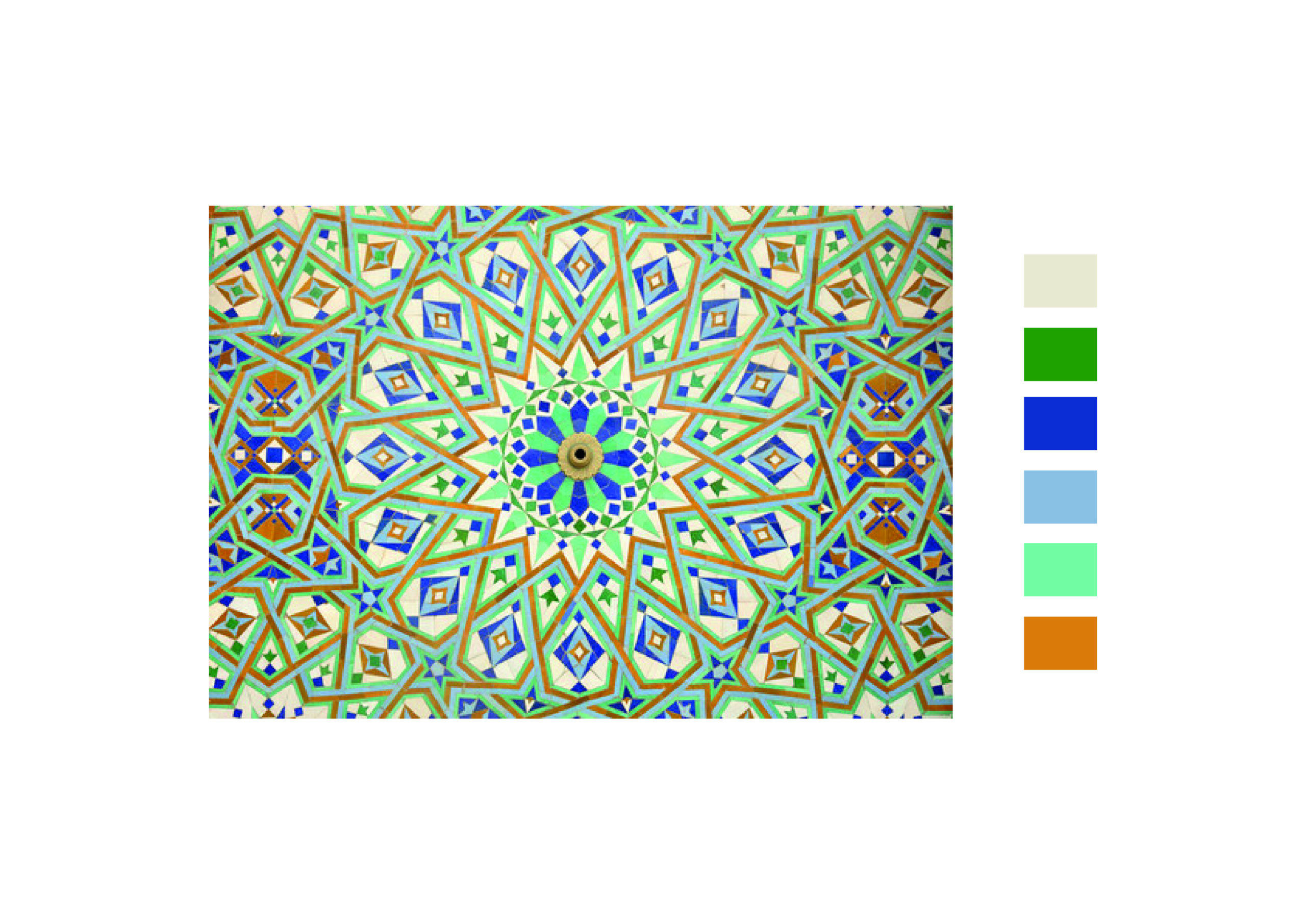

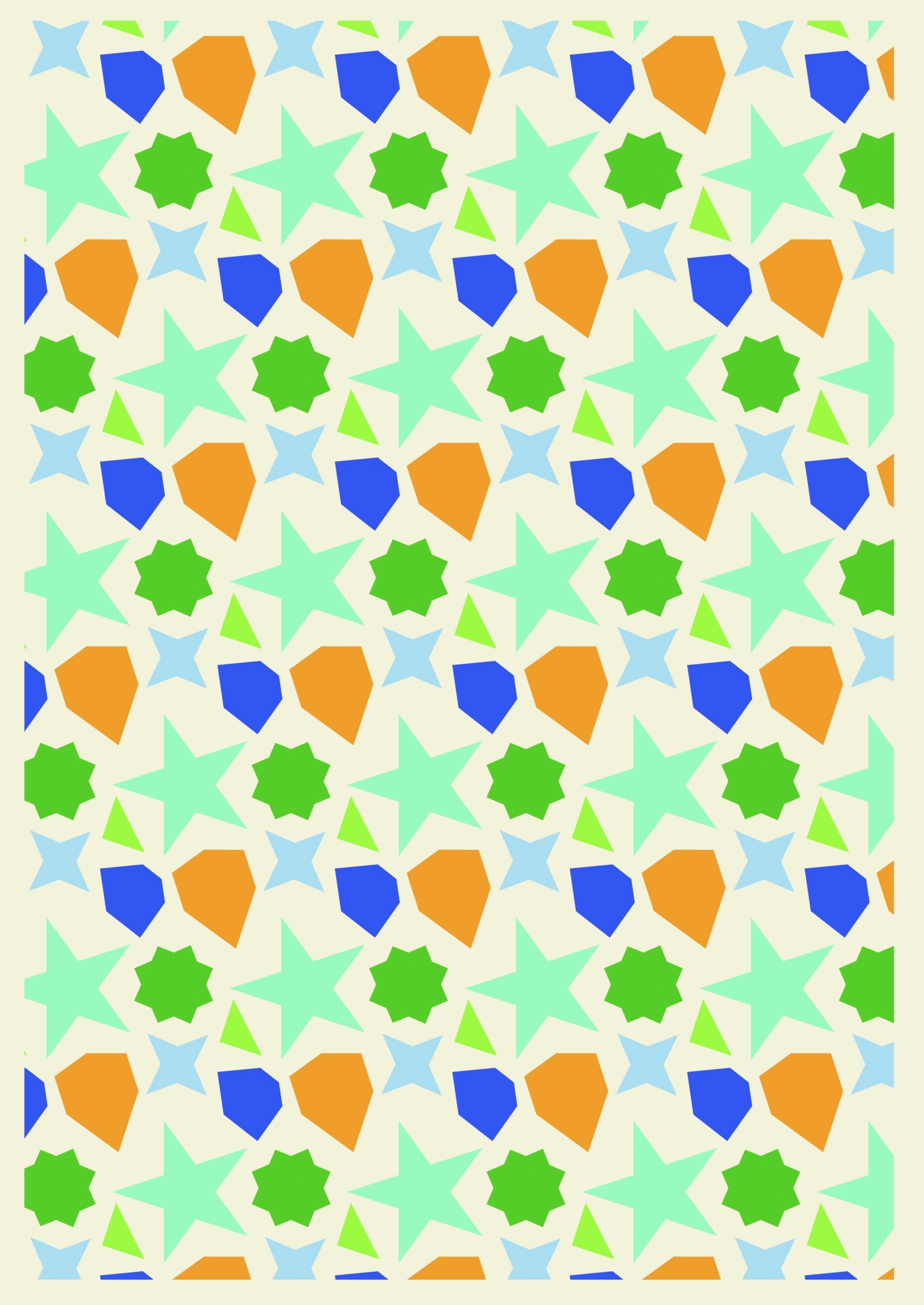

ISLAMIC GEOMETRIC PATTERNS – CHAOS PT.3

Using the colour scheme from the Islamic pattern found below, and the shapes extracted in the previous posts I’ve formed two new patterns. Although seemingly simple, this sub-project is my interpretation on the project title, making and breaking narrative. Stripping the patterns of their rigid format, thus breaking narrative, and or heritage, and making something new.

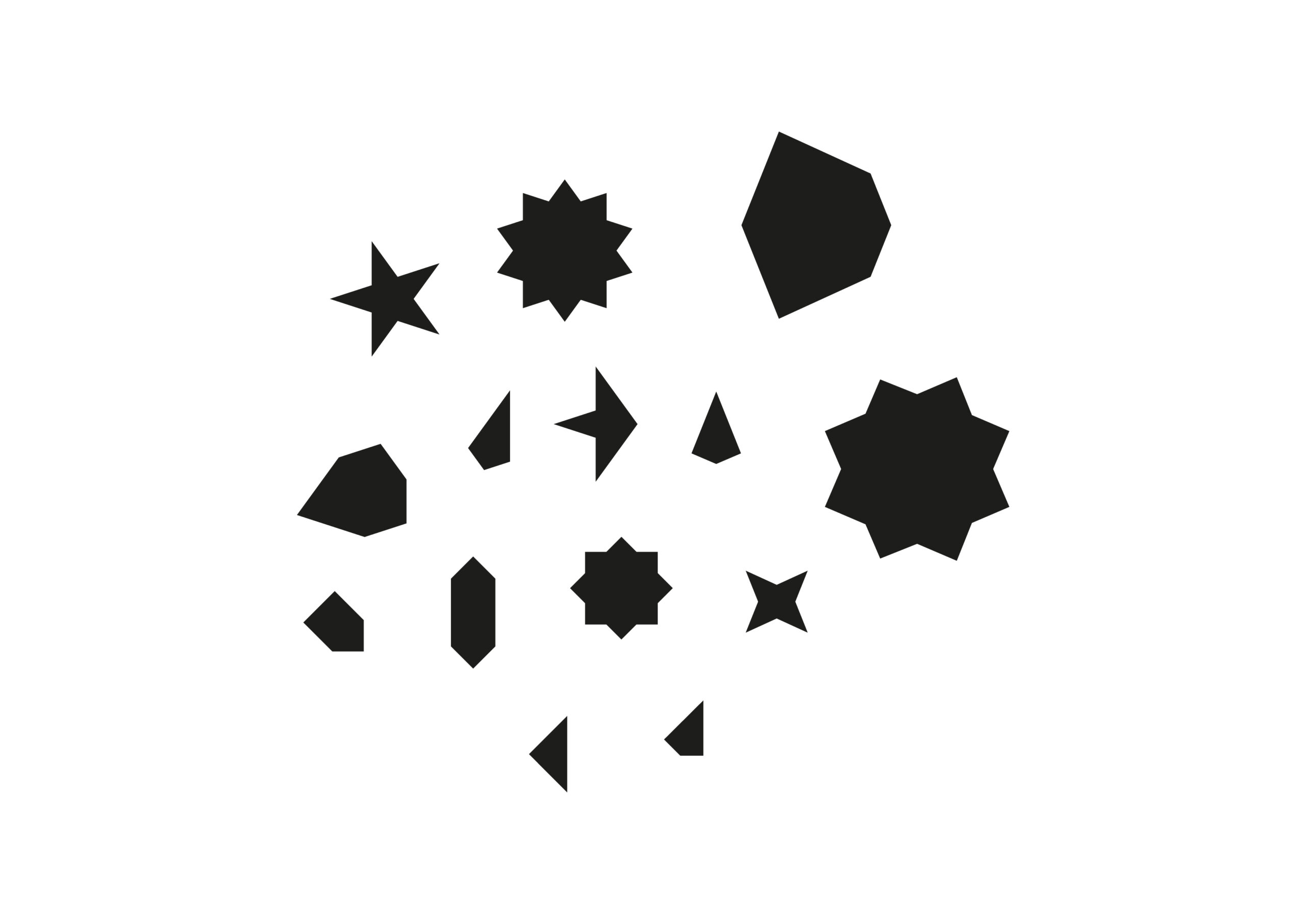

ISLAMIC GEOMETRIC PATTERNS – CHAOS PT.2

EXTRACTED SHAPES

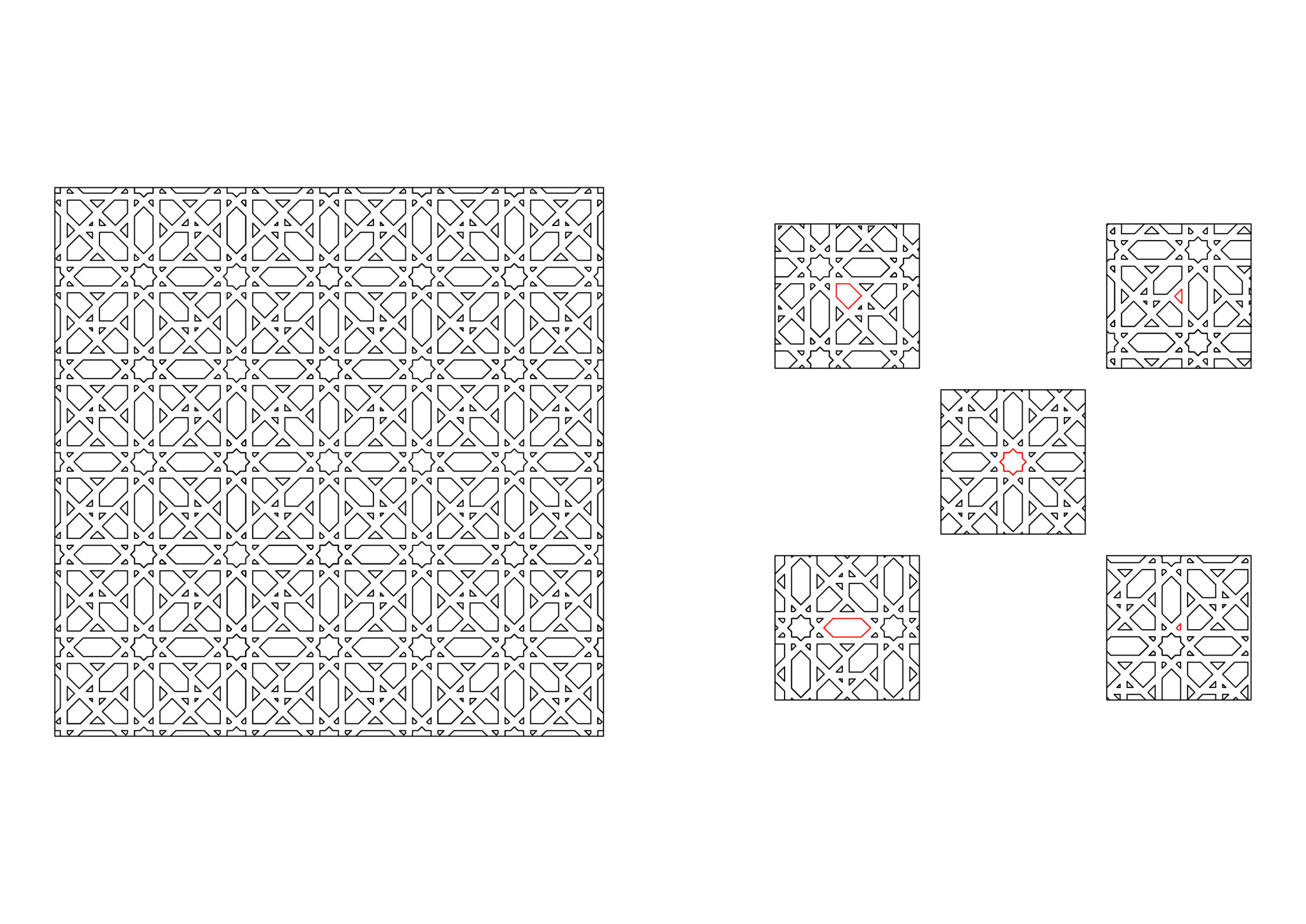

ISLAMIC GEOMETRIC PATTERNS – CHAOS PT.1

In this sub-project entitled chaos, I’ve examined three different Islamic patterns, extracting and highlighting the different shape forms found from within them.

EXTRACTING SHAPES NO.1

EXTRACTING SHAPES NO.2

EXTRACTING SHAPES NO.3

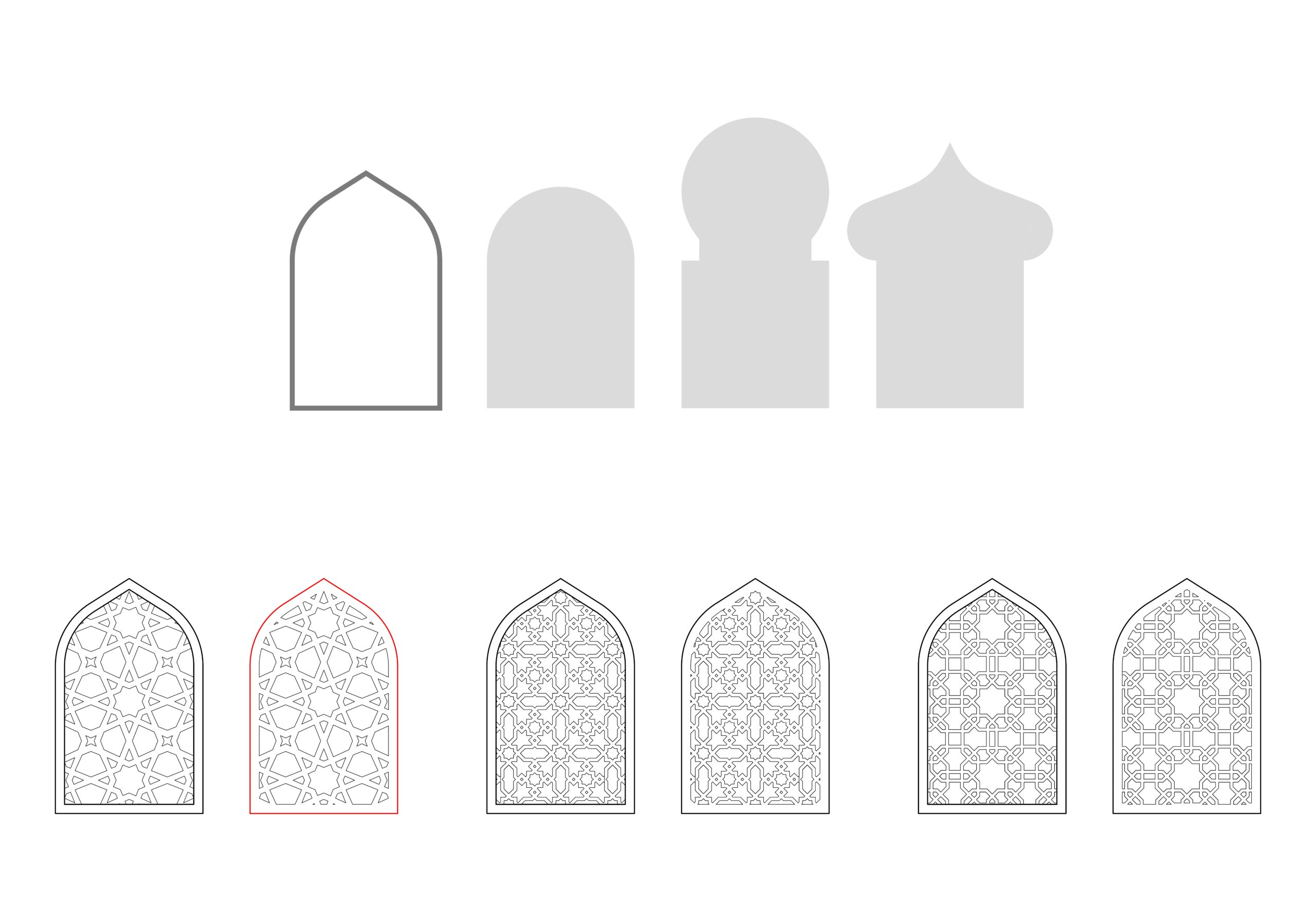

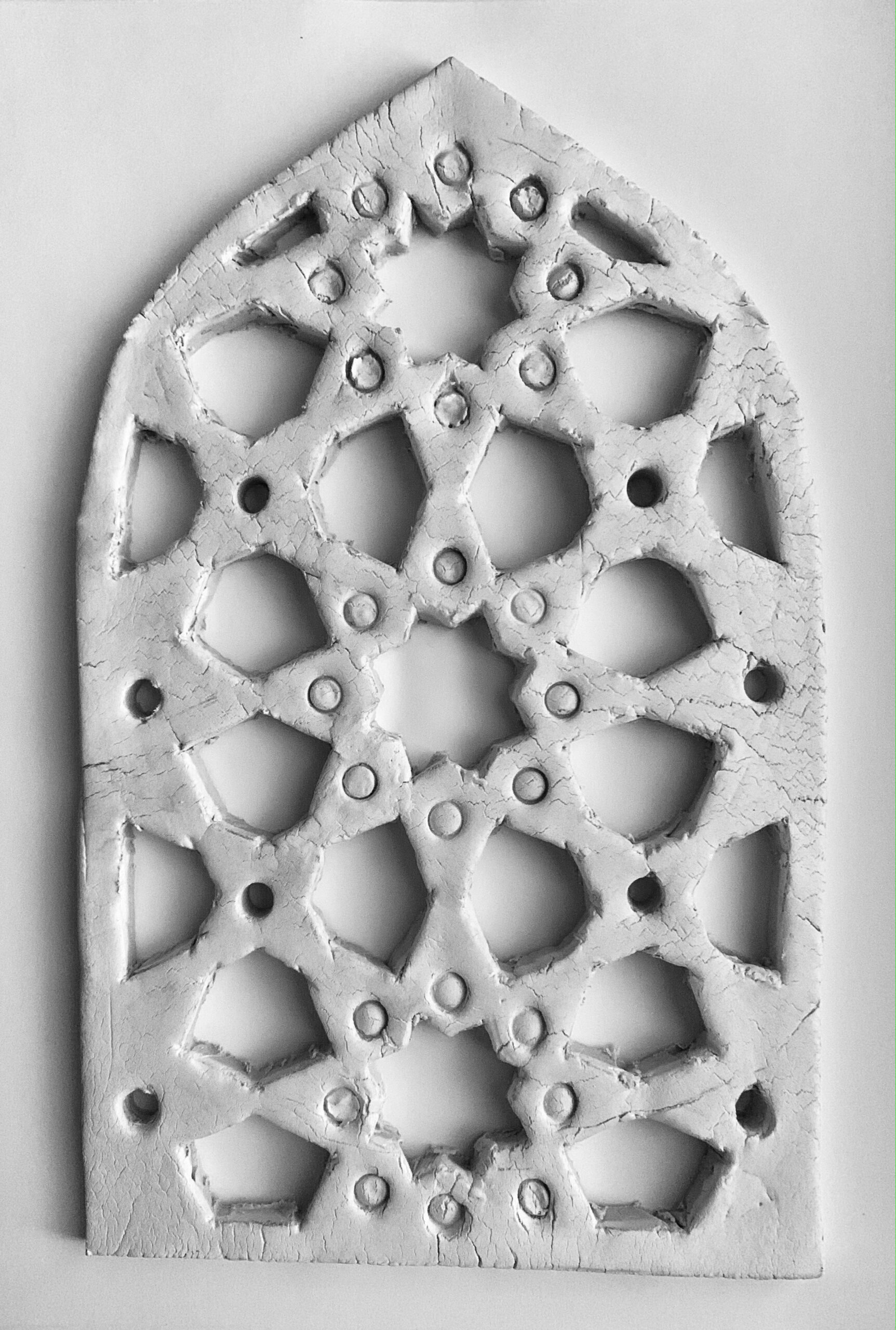

ISLAMIC GEOMETRIC PATTERNS – MASHRABIYA

Here I wanted to create a small screen inspired by the mashrabiya. To do this there were three primary decisions that had to be made: what form it would take, what pattern would exist within this form, and finally, what medium it would be completed in?

With respect to form – in the first illustration, I’ve depicted my thought process. Researching arches found within Islamic architecture, I created these 4 samples. They include – from left to right – a keel arch, a round arch, a keyhole/ horseshoe arch and a more extravagant form of an ogee arch. Of these, I chose the keel arch, for its simplicity and straight edges – making it easier to cut out – as well as its pointed arch, which I thought made it more interesting than the plain rounded arch.

The next step was choosing a pattern. Of those presented here, I chose the first, for its larger shapes which again was done so out of ease.

Lastly, I had to decide on a medium to carry my design out on. Initially, I thought about doing it in card and creating something similar to my work entitled ‘Scraps’, from working with the found object. In the end though, I went with clay. Unfortunately, the clay I used wasn’t great, whilst making it. That said, despite my difficulties with its texture and drying time, I quite like the final result.

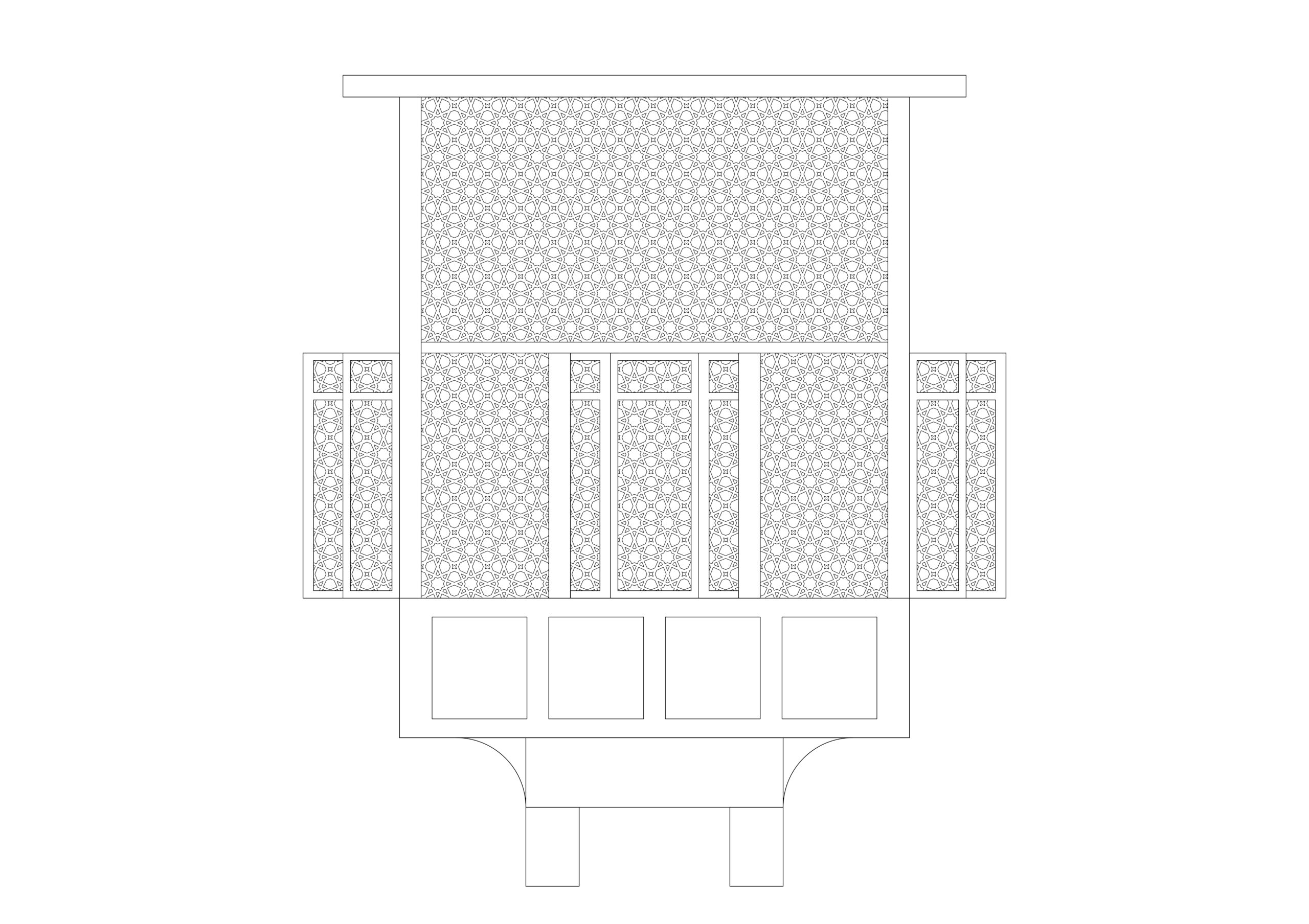

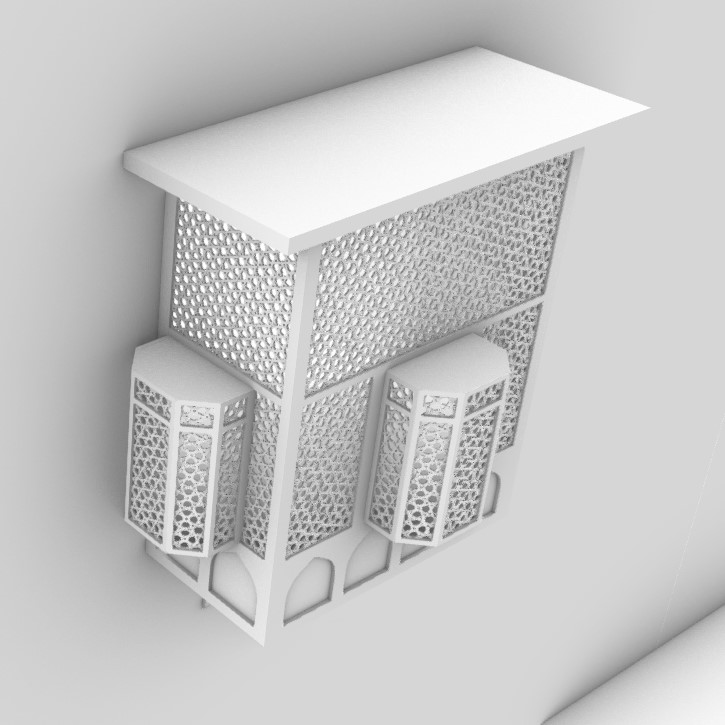

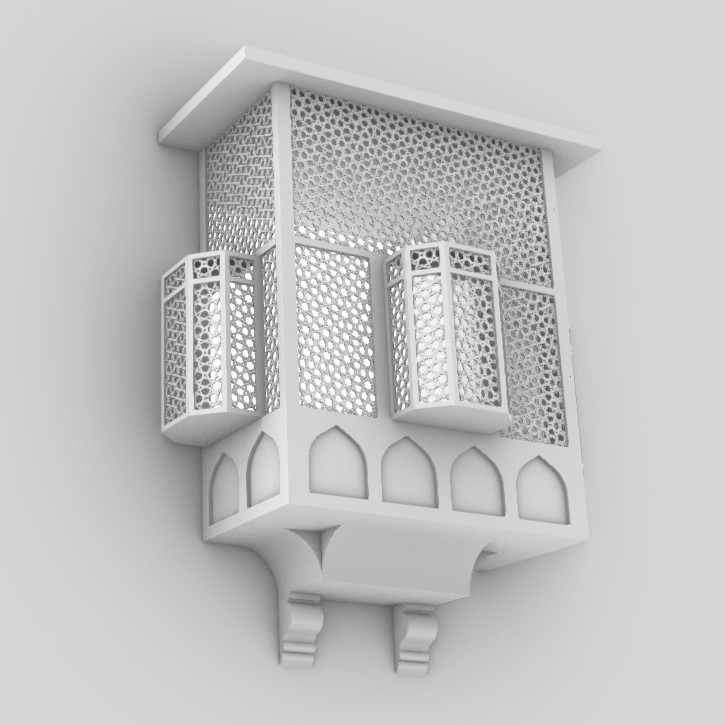

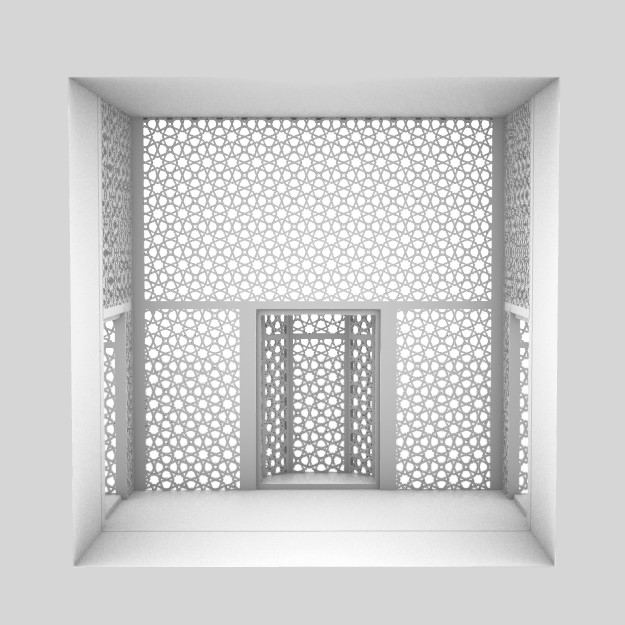

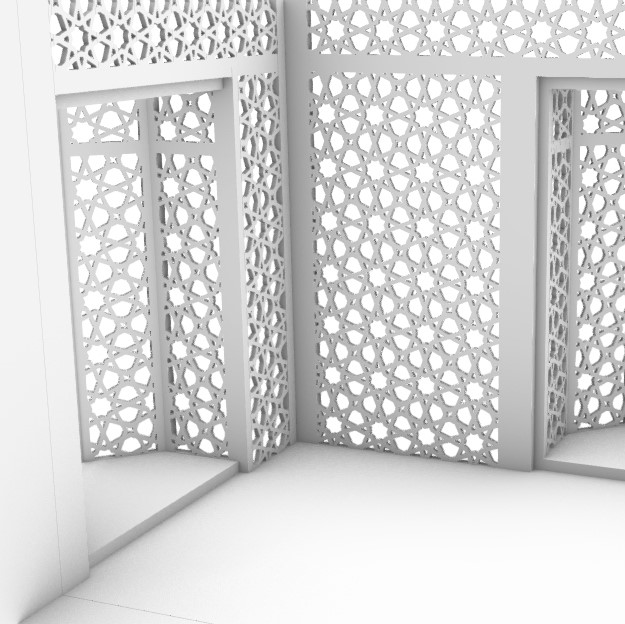

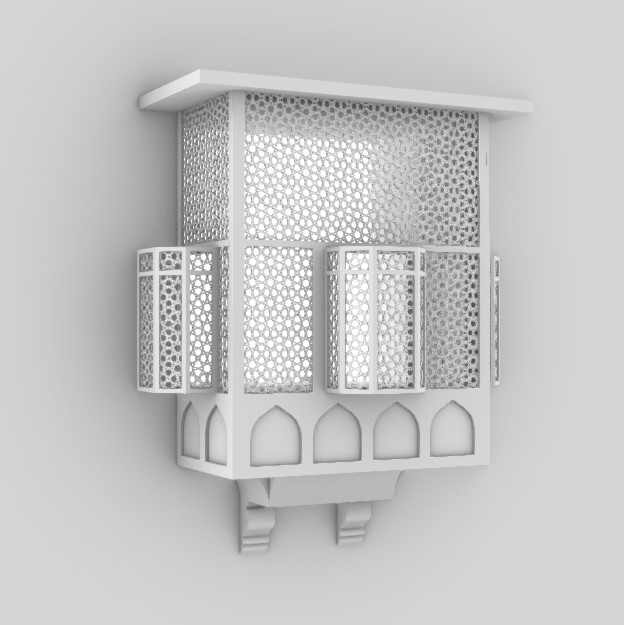

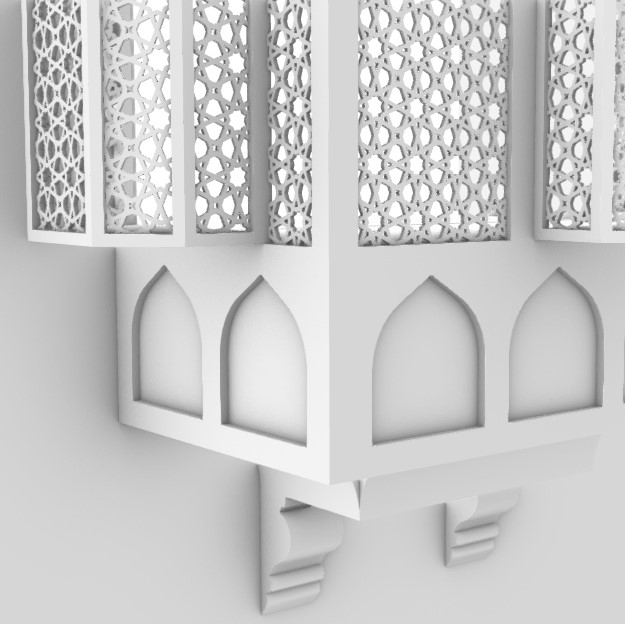

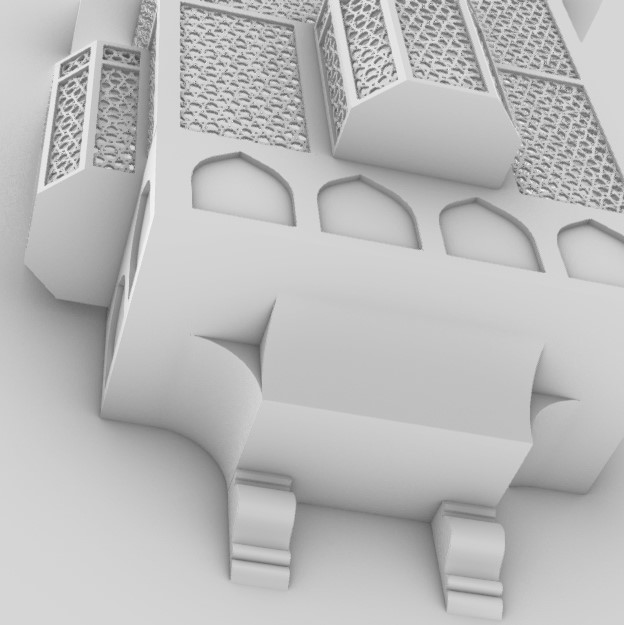

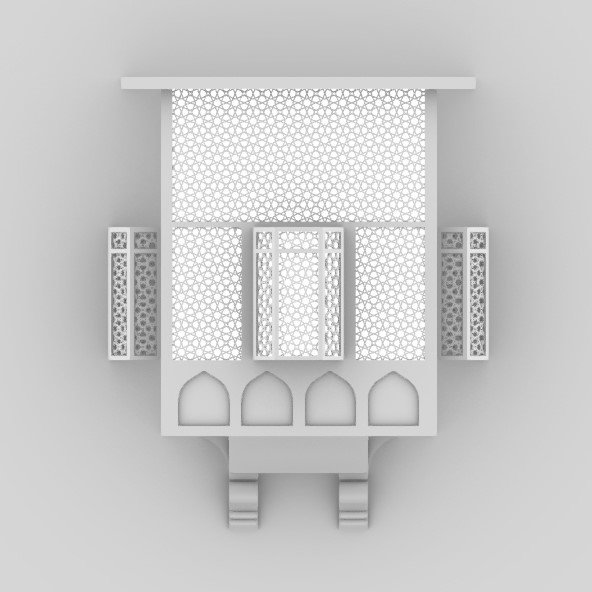

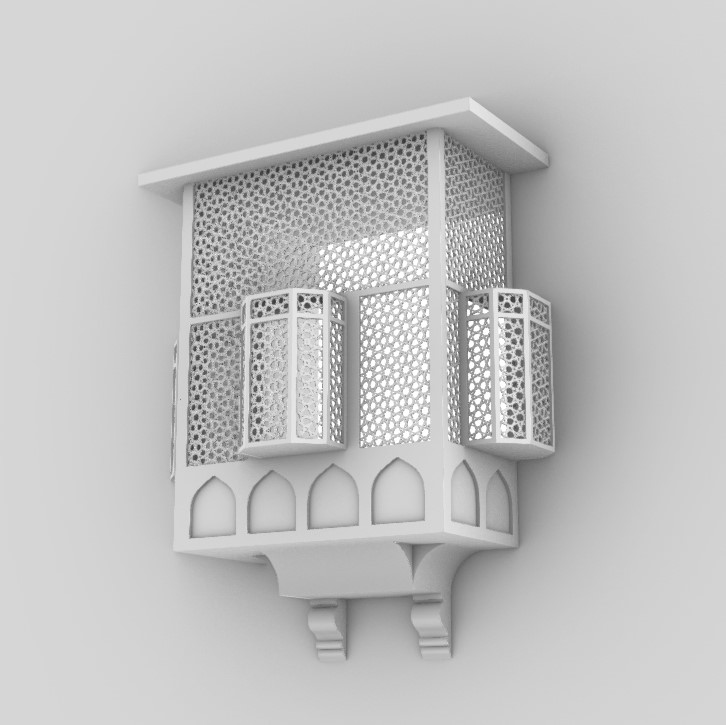

ISLAMIC GEOMETRIC PATTERNS – MASHRABIYA MODEL

Following research on the role of a Mashrabiya within Arabic life, I wanted to design one for myself. This piece is an amalgamation of elements in its form and sizing from precedents found and researched online. The model itself wasn’t too challenging to create, but the screening was particularly finicky to produce – requiring it to be re-drawn several times due to problems in extruding. In comparison to other examples, mine is relatively simple. That said, if it were completed in wood and traditionally fashioned in wood by craftsmen, it might present itself rather different entirely. In its final state, I really like how it turned out; successfully featuring the main aspects of the mashrabiya, which I’d set out to do.

The geometric pattern featured in this piece is one I’ve used throughout this sub-project, and has been chosen for its open features, promoting air circulation.

Accompanying this model I’ve included a drawing, depicting the front-facing perspective.

ISLAMIC GEOMETRIC PATTERNS – MASHRABIYA

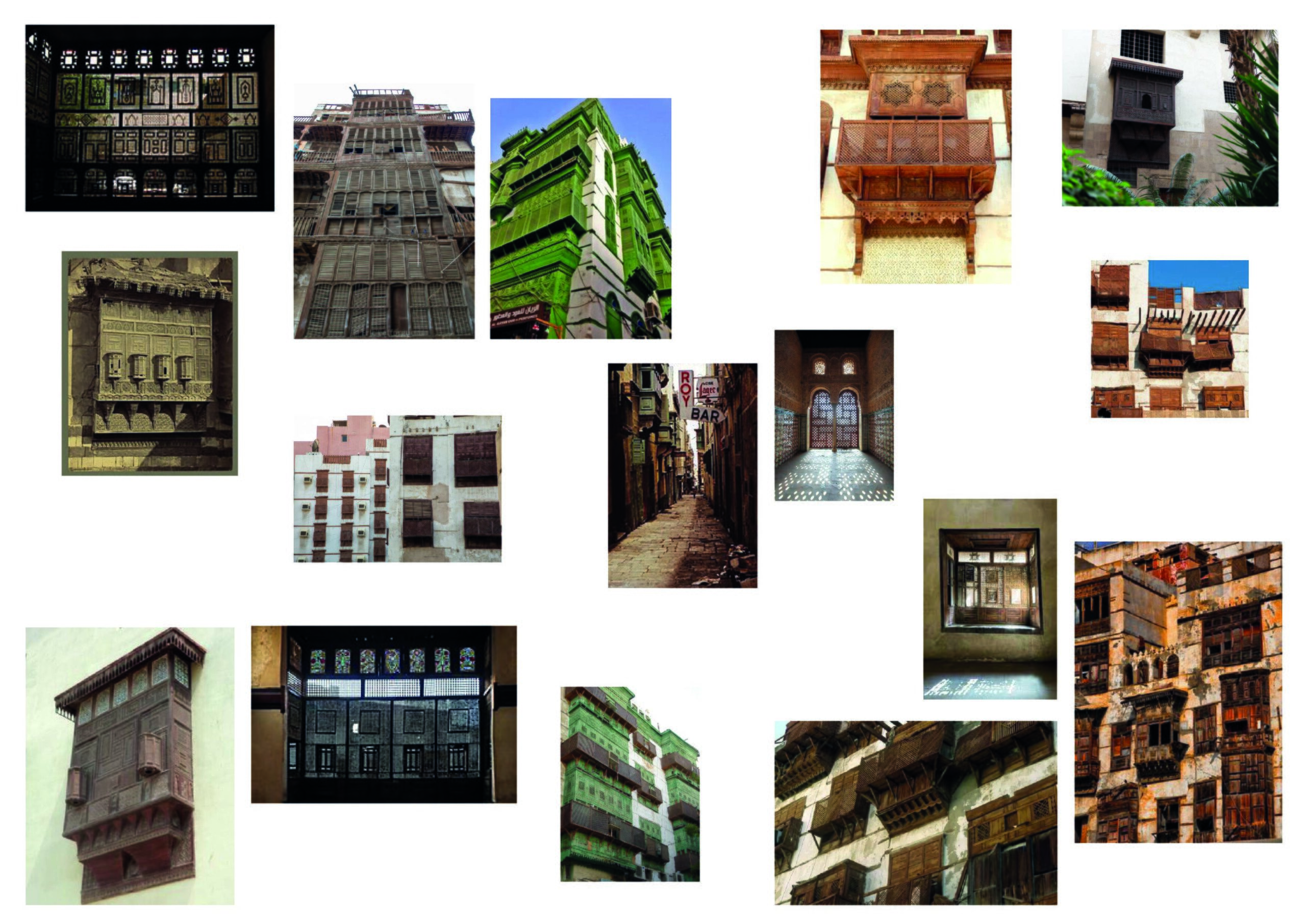

A mashrabiya, also known as either shanshūl or rūshān, is an architectural element, essential to the traditional architecture of the Islamic world. They serve as highly decorated enclosed balconies, representing cultural heritage and successfully harmonize artistic and architectural philosophy. Used since the middle ages, its approach in form draws from oriel windows – or bay windows – which protrude from the main wall of a building, without touching the ground. Responding to the cultural and geographical aspects of daily life within the ancient Islamic world, mashrabiyas strongly differ in their design from their European counterparts.

Integral to the Arab lifestyle, mashrabiyas were generally installed within domestic dwellings and royal residences – situated on the upper floors (from the first, upwards), and sometimes in open-air structures. They’re commonly employed externally, on the street side, however they can also be positioned internally, on the sahn side, facing an inner courtyard. Where they hang over onto public streets, Islamic laws require that the design and build ensure the safety of those below. The projecting component of the mashrabiya is designed such that, under no circumstance, is it to cause any damage to either neighbors, nor the occupants of the street beneath.

The construction of a mashrabiya involves a series of cylindrical wooden pieces, known as bars, which range in size from 10cm to 1m depending on both the scale and level of detail required. Creating the mashrabiya’s form, these bars are spaced out at regular distances and interconnected with larger pieces – cylindrical or cubic in shape. When completed, the joining of these elements, creates precise and decorative geometric shapes which make up the design. The horizontal bars are attached to these interconnected points using mortise and tenon joints, a strong and durable wood-joining technique, which has been used for thousands of years.

In using this technique, traditional craftsmen could assemble these screens without the need to use tools or fasteners, like nails. Using techniques like this, passed down through generations, the overall structure is able to maintain its shape, adjusting itself, as necessary, to withstand both compression and expansion in varying climates. Modern made mashrabiyas often use more high-tech methods of joinery, sometimes straying from the graceful form of the traditional façade.

In order to increase structural integrity, bars were also positioned within the framework to aid in the distribution of loads throughout the lattice. Structurally the lattice is formed of two primary sections – the upper and the lower. The upper consists of a tight lattice, made up of fine narrow bars, whereas, the lower is in more of an open grid format with broader bars.

Traditional craftsmen of mashrabiya also, through experience, are able to adapt their methods according to the wood type employed – understanding the behavioral traits of each.

Designs for mashrabiya are created by architectural designers and craftsmen alike. Wood carvings and inscriptions act as decorative elements, working alongside the geometric patterns formed from the structure of bars. Varying designs in this latticework were a result of regional aesthetics. Most mashrabiyas were sealed. This was done through the fixing of stained glass, which could be coloured, adding to the aesthetic. Alternatively, for those that weren’t, they were left open.

Aside from its decorative function, the mashrabiya’s long-established cultural value can be credited to its role in responding to both the needs of the user/ occupant, and the environmental conditions of the location.

One of the primary advantages of the mashrabiya is its protection against the high heat and intense sunlight of middle eastern climates. Due to its dry desert climate, featuring high temperature and humidity levels, methods of cooling are vital in ensuring a degree of comfort within homes. For this reason, it’s no wonder that the mashrabiya, which offers a passive cooling system, as well as shade, has been used in the region for many centuries. Traditionally it was used to capture and passively cool the wind. Jars and basins of water would be placed within it, which naturally caused evaporative cooling. These containers stored drinking water which cooled over time. When open, the mashrabiya allows for cool air to pass through the façade, promoting a constant air flow, cooling the interior space.

Due to the significant role they play in cooling, in response to the sun, when designing a mashrabiya, architects and or artisanal designers had to consider its orientation and situation in relation to the sun’s path. In positions where they are more exposed to sunlight, spacing between bands are typically narrower. From the outside, the mashrabiya presents a beautiful and enigmatic front. In the light of day the patterns present on the surface are reflected internally, creating ethereal patterns amongst the shadows. The soft diffusion of light, darkening the interior relieves occupants from what would otherwise be uncomfortably bright.

There are other advantages of the mashrabiya which concern the users’ needs. For one, the mashrabiya enables occupants from within to retain contact with the outside world, through its lattice structure (forming perforated wooden screens), all the while preserving their privacy. This privacy is emphasized due to the high luminous intensity outside and the fine dark screen of shade on the inside.

Another advantage it gives rise to relates to its surrounding architectural context. Within Islamic urban communities, the spacing relationship between buildings can be quite irregular i.e. following the contours of small winding roads. This can, at times, for homeowners or their neighbours, result in dead spaces and unconventional shapes, which can be an asset or a liability, depending upon the circumstances. This is where the mashrabiya plays another important role. Its projecting form effectively reacts to these varied shaped land plots and the spaces that lie between buildings. This can allow rooms on the upper floors to be expanded, through the space which the mashrabiya hosts, thereby expanding usable space, without having to alter the plot’s dimensions.

Finally, mashrabiya not only aids users inside; it also impacts the ground floor and the space into which it protrudes. Creating a covered area off the road, they cause large buildings, in an urban context, to feel more grounded – particularly to those outside. In addition they cast shadows and could block rain for pedestrians as well.

Overall, the ancient mashrabiya successfully merges cultural values of heritage, traditional geometric visuals and ancient technical aspects, into something beautiful that has truly stood the test of time.

ISLAMIC GEOMETRIC PATTERNS – MEDIUMS

The tradition of making geometric patterns within Islamic art has lasted over a millennium. Through the wielding of the basic principles of geometry, works found in both religious and secular contexts, in an array of media – from ivory to glass – provide an intricate and complex glimpse into the spiritual world.

Thanks to the diversity in pattern formations, varying in complexity, they work effectively in an array of mediums, fitting to various forms – whether that may be a stone carving, a tiled wall etc. This versatility in the creation of art allowed it to develop and flourish within Islamic culture, as it could, and would be used to adorn everything in both religious and non-religious contexts.

Within the framework of religion, for centuries, Islamic geometric patterns have been employed as decorative elements, within the architecture of mosques (and other buildings), on walls, ceilings, doors, domes and minarets. The same can be said for domestic items; they also feature in books and textiles, imparting significance and value.

Below I’ve created a collage, exploring the primary mediums used by craftsmen, accompanied by an example, sourced to its origin and date of creation.