What Kendrick Lamar’s modern day ‘Sorrow Songs’ can tell us about territorial stigmatisation in Compton

Compton, Los Angeles, is a neighbourhood stigmatised as a black ghetto, supposedly afflicted by gang violence and drugs, which has become globally notorious. Strikingly, that notoriety has partly been fuelled by the art of black rap artists. Rap artist Kendrick Lamar comes from Compton, but he does not glamorise gang culture. Khalil Joseph’s ‘Double Conscience’ (later renamed m.A.A.d) is a 14 minute film made from footage shot to accompany Kendrick on stage supporting Kanye West in 2013. The full double-screened film is not available online, so I will be using the available footage and knowledge from my viewing at the Infinite Mix. The film features music from Kendrick’s album ‘good kid, m.A.A.d city’, an acronym with double meaning: ‘my Angry Adolescence divided’ and ‘my Angels on Angel dust’. Intriguingly, the film’s original title refers to celebrated black sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois’s theory of ‘double-consciousness’, from the dawn of the twentieth century [1], which describes the internal conflicts suffered by African Americans in a racist society, forced to see themselves not just as themselves but as they are seen by that society. Through the art of Khalil and Kendrick, I will explore the territorial stigmatization [2] of Compton, and its relationship with the idea of double-consciousness. Art and place are often connected and, as Tim Cresswell puts it, there is ‘art of place, where art attempts to represent place’ [3] . That is especially powerful where, like Khalil and Kendrick, the artist has special insight into and experience of that place.

I will start by introducing the history of housing in Compton, then explore the idea of stigmatisation and finally analyse the art of Khalil and Kendrick and their depiction of life and stigmatisation in Compton. My argument is that their art, infused with the idea of double-consciousness, elucidates how residents of Compton experience and resist territorial stigmatization.

Compton

Until just after WWII, Compton was a largely white, middle-class neighbourhood. Housing covenants initiated by whites in 1921 had excluded blacks from Compton [4]. However, from the end of WWII to the 1960s Southern California experienced a great black migration into areas such as Watts, Willowbrook, and Avalon, which neighboured Compton. These areas became cramped, and when the exclusionary housing covenants were effectively abolished following Supreme Court decisions in 1948 and 1953, many black families moved into Compton, often those with double incomes on the back of the industrialization of LA [5]. By 1960 40% of Compton residents were black, but it remained a middle-class community [6].

It was not until 1965 that the Watts Riot sparked rapid white flight from Compton, which also removed businesses and therefore jobs and tax revenue. At the same time the Californian economy was beginning its long deindustrialisation, which continued into the 1990s, with 200,000 jobs lost in LA between 1978 and 1990, mostly in the South Central area [7]. Combined with an influx of 1 million immigrants over the same period, this resulted in high unemployment, particularly amongst Compton’s youth. Many turned to the illegal drug economy as the most reliable source of employment. Gang battles for control of the crack market led to black-on-black street violence. In 1973 the Los Angeles Times described Compton as a ‘ghetto of poverty, crime, gang violence, unemployment and blight’ [8].

Films such as ‘Boyz in the Hood’ and rap albums such as ‘Straight Outta Compton’ by NWA (Niggas With Attitude) helped to make Compton globally notorious [9]. Even though crime rates are now dropping [10], Compton remains stigmatised as the home of the gangs and drugs that once controlled its streets.

Territorial stigmatisation

Stigmatisation is both a psychological and a social phenomenon, described by Erving Goffman in the 1960s as ‘spoiled identity’ [11] and a process in which people’s differentness is ‘discredited’. Loic Wacquant’s book ‘Urban Outcasts’ applied those ideas to urban neighbourhoods with the idea of ‘territorial stigmatisation’, to explain the way in which whole districts become disparaged and tainted, and with them the people who live there [12]. Wacquant applied the ideas of Pierre Bourdieu [13] to show how authoritative voices such as the state and various forms of media can make certain representations of groups and places ‘stick’ symbolically, even if not objectively accurate. Wacquant also grasped the multi-faceted significance of places in cities, as not only physical parts of the city and sites of social interaction but also themselves the subjects of image and reputation. So a place can have a ‘spoiled identity’ and people can be stigmatised by the stigma attaching to the places where they live [14].

As in Compton, there is often a racial element to territorial stigmatisation, as stigmatising voices in the media and elsewhere tend to emphasise, and even exaggerate, the racial composition of the population [15].

Territorial stigmatisation can have multiple effects, for example on how state officials decide how to police a place such as Compton, whether a business decides to set up there or whether an employer decides to employ a Compton resident [16]. However, one of the most pervasive effects is on the psychology and social relations of the residents, potentially corroding their self-worth, distorting their social relations and reducing their capacity for collective action, thus exacerbating their and their neighbourhood’s stigmatization [17]. For example, people may internalize the stigma, perhaps trying to avoid it personally by blaming it on other residents [18], or trying to hide their address in fear of rejection.

Others, however, take pride in the stigmatisation, feeling empowered by the fear it instills. Compton’s reputation for gangs, street violence and drugs was embraced and embodied by rap artists [19]. They glamorised gang culture to sell their music, which further stigmatised Compton – a deeply ambiguous development, in which some members of the stigmatised community-generated wealth entirely legally from the stigmatisation of their home and in so doing increased that stigma.

The experience of stigmatisation through the art of Khalil and Kendrick

Although Kendrick does not glamorise gang culture, he does not shrink from the problems of the neighbourhood where he grew up. His lyrics in ‘good kid, m.A.A.d city’ include ‘Brace yourself/I’ll take you on a trip down memory lane..’ and he uses his music to tell the stark reality of what it was like to grow up in Compton through his and others’ experiences. Through his autobiographical account, we can understand the daily experience of territorial stigmatisation.

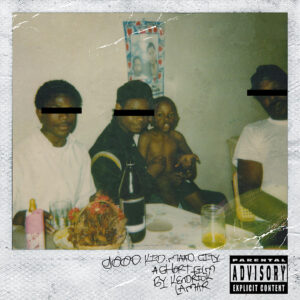

Good kid, m.A.A.d City album cover. From https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/9/93/KendrickGKMC.jpg.

The album art features a photo of Kendrick as a child and 3 members of his family with their eyes blacked out, alluding to the search in the album for the true story of Compton during his youth through his innocent young eyes. Kahlil expresses this same search through the use of home footage from Kendrick’s youth in 1992 that is interspersed throughout the film.

The film and music both highlight the gang culture that Kendrick was exposed to when growing up. Immediately at the start of the film we are introduced to the Pirus and Crips (two notorious gangs in Compton) through Kendrick’s lyrics:

‘If Pirus and Crips all got along

They’d probably gun me down by the end of this song

Seem like the whole city go against me’

Compton’s drive-through funeral. A screenshot from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4fLKcHu-LJo&list=RD4fLKcHu-LJo&start_radio=1&ab_channel=ZweiOptionenArschOderMundauf.

Matching this, the first minute of film is chaotic, featuring gang violence and culture, but then abruptly stops and focuses in on a drive-through funeral (1:05), bringing us down to the harsh reality of living in Compton. Drive-through funerals became popular when gang violence was at its peak as gangs did not want to gather for a funeral for fear of attack.

Kendrick then highlights the stigma of gang violence that is attached to Compton and himself in his lyric:

‘If I told you I killed a nigga at sixteen, would you believe me?

Or see me to be innocent Kendrick you seen in the street

With a basketball and some Now and Laters to eat?’

Here he both sees himself through the eyes of others, in playing on the stigmatisation that he has been subjected to, yet is still able to see himself differently through his own eyes – Du Bois’s ‘double-consciousness’ and the original title of Khalil’s film. This is also visually represented in a multitude of ways, including the use of two screens, angled towards each other so that, if they were two mirrors, we the audience would be able to see ourselves twice.

Concluding thoughts

Imogen Tyler describes Du Bois’s work in the early twentieth century as weaving together ‘autobiographical experiences, the “Sorrow Songs” of black spirituals, social history, and economic and statistical data into a shattering account of the “studied humiliations” of anti-black racism.” [20]. This finds echoes in the autobiographical art of Khalil and Kendrick, whose music is the contemporary equivalent of Du Bois’s “Sorrow Songs” – expressions of the experience of suffering societal racism. This art therefore adds a rich dimension to the understanding of Compton’s territorial stigmatisation and how it is experienced, in particular showing how territorial stigmatisation forces double-consciousness on the black residents of Compton.

This art also shows, however, that Tyler is right to suggest that ‘the double-consciousness which being stigmatised effects is a resource for resistance’ [21]. Kendrick and Kahlil use this double-consciousness not only to express their own experiences to a wide audience but to question the social, economic and political systems that generate such stigmatisation. They use the high public profile of their art not only to expand understanding but to hold a critical mirror up to the whole of society.

I want to leave the last words to Kendrick. He looks to the future, with the same double-consciousness, but also a hope that society’s perceptions of black Americans might evolve to make it redundant:

‘And it’s safe to say that our next generation maybe can sleep

With dreams of bein’ a lawyer or doctor

Instead of boy with a chopper that hold the cul-de-sac hostage’.

Kahlil Joeseph ‘Double Conscience’ at the MOCA. Photo from https://www.moca.org/exhibition/kahlil-joseph-double-conscience.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (1999) ‘The souls of black folk. Critical edition’. H. L. Gates Jr & T. H. Oliver. (Eds.). New York, NY: Norton (Original work published 1903). Pp 10-11.

- Wacquant, L. (2008) ‘Urban Outcasts A Comparative Sociology of Advanced Marginality’. Polity press, Cambridge.

- Cresswell, T. (2015). ‘Place an introduction’ (second edition). John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Sussex.

- Sides, J. (2004). ‘Straight into Compton: American Dreams, Urban Nightmares, and the Metamorphosis of a Black Suburb’. 56:3 pp583-605. American Quarterly Los Angeles and the Future of Urban Cultures.

- ANON (1953). ‘California Eagle’. Cited in Sides, J (2004), pp. 585.

- Sides, J. (2004).

- Sides, J. (2004).

- Jean Douglas Murphy, Doris Davis Running Hard and Fast, Los Angeles Times, (September 23, 1973 cited in Sides 2004 pp. 596), sec. 10, 1, 18.

- Contreras, R. (2017). ‘There’s no sunshine: Spatial anguish, deflections, and intersectionality in Compton and South Central’. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space. 35:4 pp 656-673.

- Contreras, R. (2017).

- Goffman, E. (1963). ‘Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Simon and Schuster’, New York.

- Wacquant, L. (2008).

- Bourdieu, P. (1991). ‘Language and Symbolic Power’. Polity Press, Cambridge.

- Wacquant, L., Slater, T., Pereira, V.B. (2014). ‘Territorial stigmatization in action’. Environment and Planning A. 46, pp 1270-1280.

- Wacquant, L., Slater, T., Pereira, V.B. (2014).

- Wacquant, L., Slater, T., Pereira, V.B. (2014).

- Wacquant, L., Slater, T., Pereira, V.B. (2014).

- Contreras, R. (2017).

- Contreras, R. (2017) and Wacquant, L., Slater, T., Pereira, V.B. (2014).

- Tyler, I. (2020). ‘Stigma The Machinery of Inequality’. ZED Books, London. pp239.

- Tyler, I. (2020). pp240.

Recent comments