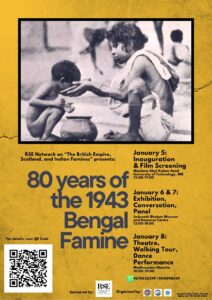

Conferences and Public Events — Edinburgh, Guwahati, Kolkata

80 years of the 1943 Bengal Famine: Remembering through Talks and Events

(Under the RSE Research Network Grant for the Project “The British Empire, Scotland, and Indian Famines: Writings on Food Crisis in Colonial India”, Gr. No. 69777)

January 5-8, 2024

DAY 1, JANUARY 5

Venue: Maulana Abul Kalam Azad University of Technology (MAKAUT), WB, Auditorium, XG5V+27R, Haringhata Farm, West Bengal, 741249

12.00-13.00: Opening Ceremony

Welcome (Dr. Rajarshi Mitra, Dr. Sourit Bhattacharya, and Dr. Binayak Bhattacharya)

Formal inauguration by Vice Chancellor, MAKAUT, WB, Prof. Tapas Chakraborty

Address by Vice Chancellor

Speech by dignitaries

14.00-16.30: Film Screening followed by discussion

Film: Akaler Sandhane (In Search of Famine, Dir. Mrinal Sen, 1982)

Discussant: Dr. Manas Ghosh (Jadavpur University)

Moderator: Dr Binayak Bhattacharya (MAKAUT, WB)

DAY 2, JANUARY 6

Venue: Jadunath Bhavan Museum & Resource Centre (JBMRC), 10 Lake Terrace, Kolkata – 700029

12.00: Inauguration of the Exhibition: Monone Ponchash: Monontwor Fire Dekha

(’43 in the Mind: Re-visiting the Great Famine)

12.00-12.30: Inaugural Discussion:

Dr. Somshankar Ray, curator, in conversation with Dr Binayak Bhattacharya:

Topic: How do we re-visit the traumatic pasts of the famine?

13.30-14:00: In Conversation:

Dr Sourit Bhattacharya (University of Edinburgh), Dr Rajarshi Mitra (IIIT Guwahati), and Dr Binayak Bhattacharya (MAKAUT, WB) on:

Topic: Why did we organize this event and where to go from here?

15:00-15.30: In Conversation

Discussants (TBC)

Topic: Archiving the Famine: Challenges and Possibilities

16.30-17.30: In Conversation:

Dr Trina Nileena Banerjee (CSSSC) & Prof Sanjoy Kumar Mallik (Visva-Bharati University) with Dr Rajarshi Mitra on:

Topic: IPTA, artwork, and the famine

17.30-19.00: Exhibition closes for the day

DAY 3, JANUARY 7

Venue: Jadunath Bhavan Museum & Resource Centre (JBMRC), 10 Lake Terrace, Kolkata – 700029

12.00–19.00: Exhibition: Monone Ponchash: Monontwor Fire Dekha

(’43 in the Mind: Re-visiting the Great Famine)

12.00-12.30: In Conversation

Sumantra Baral and Aryama Bej with Dr Rajarshi Mitra:

Topic: The Famine in Scholarly- and Art-work for the Future

14.00-14.45: In Conversation

Dr Janam Mukherjee (Toronto Metropolitan University) with Dr Sourit Bhattacharya:

Topic: War, Famine, and the End of Empire: Re-visiting the topic today

16.00-18.00: Panel: How Do We Preserve the Memories of the 1943 Famine? On Archiving a Catastrophe

Venue: Barun De Auditorium, Jadunath Bhavan Museum & Resource Centre

Discussants: Prof Supriya Chaudhuri (Jadavpur University)

Mr. Madhumoy Pal (Writer and Ex-Journalist, Aajkal)

Prof Abhijit Gupta (Jadavpur University)

Dr Md Intaj Ali (Netaji Subhash Open University)

Dr Rituparna Roy (Kolkata Partition Museum)

Moderator: Dr Sourit Bhattacharya

18.00-19.00: Closing of the Exhibition

DAY 4, JANUARY 8

Venue: New Market Area, Kolkata

08.00-10.00: Walk through urban sites associated with the WWII and the

1943 Bengal Famine: “A Tour through Hunger”

Guide: Dr Tathagata Neogi (Immersive Trails)

Venue: Madhusudan Mancha, G958+9H3, Gariahat South, Jodhpur Road, Dhakuria, Kolkata – 700031

12.00–21.00: Film Screening, Performance, Discussion

12.00-14.00: Film Screening

Dharti Ke Lal (Children of the Earth, Dir. K.A. Abbas, 1946)

14.30-15.30: Panel Discussion

Discussants: Prof. Sanjoy Mukhupadhyay (Jadavpur University) & Prof. Anuradha Roy (Jadavpur University); Moderator: Dr Binayak Bhattacharya

16.30–17.30: Song and Dance Performance:

Mr. Shubhendu Maity

Ms. Aryama Bej

18.30-20.30: Theatre Performance and Discussion:

Jabanbandi (Confession, 1944) by Bijon Bhattacharya

Produced and staged by: Anandapur Gujob (Independent Theatre)

Introduction: Mr. Samik Bandopadhyay (art and theatre critic)

Post-Theatre Discussion and Q&A

20.30-21.00: Closing remarks and Vote of Thanks

21.00– Closure of the Event

————————————————————-

Public Lecture on

“Climax of the Clearances: The Great Highland Famine and Scottish History”

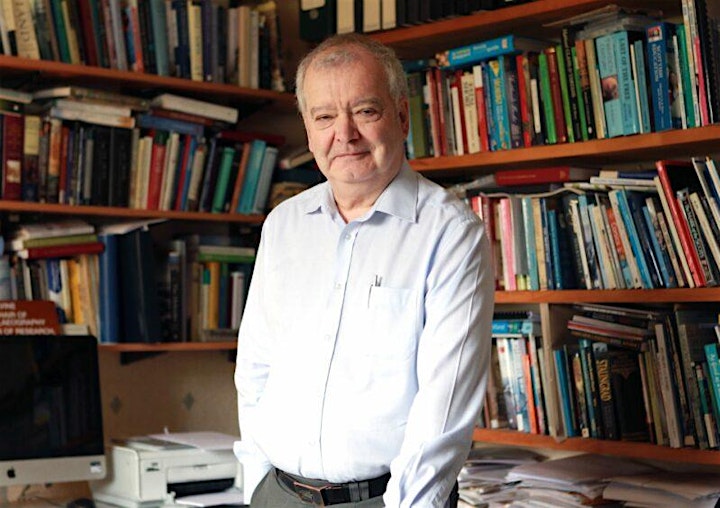

Speaker: Prof Sir Thomas Devine, University of Edinburgh

5pm-7pm, 23rd May 2023

Usha Kasera Lecture Theatre, Old College, University of Edinburgh

This public lecture sees Sir Tom Devine consider the impact of the potato blight in Scotland, and particularly in the Highlands. Devine will examine the unique history and agriculture of a landscape so dependent on the crop, and argue that it clearly contributed to the Scottish Clearances.

It is organised by the Royal Society of Edinburgh Research Network on The British Empire, Scotland, and Indian Famines.

About the lecture

This lecture considers the impact of the 1840s European potato blight on Scotland. It will focus especially on the Highlands, where over-dependency on the crop for subsistence exposed the people of the region to acute life-threatening crisis.

The first part of the lecture will seek to determine the impact of the potato failure on the people and therefore attempt to answer the question: ’Did the Highlands starve’? Throughout, comparisons and contrasts will be drawn with the Great Irish Famine (an Gorta Mór) which has attracted much more scholarly and popular attention than the famine in Scotland.

The second part will argue that the famine in the Highlands triggered an unprecedented scale and intensity of ‘clearance’, or forced removal of people from their traditional holdings, which rendered entire districts bereft of human habitation through to the present day. One eye witness government official at the time feared the evictions were so extensive as to ‘threaten the very structures of society in these parts’.

About the speaker

Sir Thomas Martin Devine (Kt OBE DLitt FRHistS HonMRIA FRSE FBA Member Academy of Europe) is Sir William Fraser Professor Emeritus of Scottish History and Palaeography in the University of Edinburgh, the world’s oldest and most prestigious chair in the field.

Devine is the author and editor of some forty books plus numerous articles and chapters across a range of historical topics since the sixteenth century to the present including The Great Highland Famine: Hunger, Emigration and the Scottish Highlands in the Nineteenth Century and The Scottish Clearances: A History of the Dispossessed 1600-1900. He also has a high media profile in the press, radio and TV, both at home and abroad.

Devine’s many honours and prizes include the Royal Medal of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotland’s supreme academic accolade and the Lifetime Achievement Award of the UK Parliament in History and Archives. He was knighted in 2015 by the late HM The Queen ‘for services to the study of Scottish history,’ the only scholar honoured for that reason to date.

About the research strand

This event is organised by the Royal Society of Edinburgh Research Network on the British Empire, Scotland, and Indian famines.

The Network is a collaboration between the University of Edinburgh and two institutions in India, IIIT Guwahati in Guwahati and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad University of Technology in West Bengal.

The Principal Investigator of the Network is Dr Sourit Bhattacharya, Lecturer in Global Anglophone Literatures at the University of Edinburgh.

Over a number of projects on the British empire and cultural responses to famine, Dr Bhattacharya’s aim is to historicise contemporary debates on neo-colonialism and global food crisis, and indigenous responses to them.

Access and recording

Please note that this is a free, in-person event held on the University of Edinburgh campus. It will not be live streamed – tickets are for access to the venue. However, the event may be photographed and/or recorded and added to the University website afterwards. If you would prefer not to appear in any recordings, please contact us in advance or speak to us on the day. It’s not a problem.

The British Empire and Colonial Famines: History, Culture, Critique

Third & Final Conference (Workshop)

University of Edinburgh

May 24-25, 2023

Wednesday, May 24

9.00-9.15: Opening Remarks; Snacks, Tea/Coffee

9.15-10.45: Panel 1 (Witnessing and Testimony)

Prof Supriya Chaudhuri (Jadavpur University): “Witnessing Famine: Ethics, Representation, Art”

Dr Diya Gupta (City, University of London): “Hunger and the Homeland: Considering Wartime Photographs and Letters on the 1943 Bengal Famine”

10.45-11.00: Break

11.00-12.30: Panel 2 (From Profit to Rebuilding)

Dr Janam Mukherjee (Ryerson University): “Boom Time: Big Business and Famine in Bengal”

Dr Benjamin Siegel (Boston University): “Bengal, Revisited? India’s 1951 Food Crisis and the Postcolonial Quest for Indian Self-Reliance”

12.30-13.30: Lunch

13.30-15.00: Panel 3 (The Politics of Famine Relief)

Dr Joanna Simonow (University of Heidelberg): “Transnational Famine Relief and Anti-Colonial Politics on the Eve of Independence”

Dr Abhijit Sarkar (University of Oxford): TBC

15.00-15.15: Break

15.15-16.45 Panel 4 (Women, Body, and Labour)

Urvi Khaitan (University of Oxford): “‘My Body Costs Five Hundred Rupees’: Women’s Work in War and Famine”

Dr Sona Datta (Freelance Curator, Writer, and Broadcaster): “From the Academic to the Actual: How Hunger is still used as an Instrument of Violence against the Body”

16.45-17.00: Break

17.00-18.30: Panel 5 (Cinema, Art, and Affect)

Dr Anuparna Mukherjee (Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Bhopal): “The Famished City: Displacement and the Trails of Hunger in Calcutta of the 1940s”

Dr Binayak Bhattacharya (Maulana Abul Kalam Azad University of Technology): “The 1943 Bengal Famine and Cinema of the Left, circa 1940s”

Day 1 ends.

——————————————————————-

Thursday, MAY 25

9.00-9.15: Snacks, Tea, Coffee

9.15-10.45: Panel 6 (Famine Prevention)

Dr Aparajita Mukhopadhyay (University of Kent): “Famine and Railways in Late 19th century Bengal: A View from the Railway Records”

Prof Vinita Damodaran (University of Sussex): “Climate Signals Droughts, Floods and Famines in South Asia”

10.45-11.00: Break

11.00-12.30: Panel 7 (Looking Back, Looking Ahead)

Dr Rajarshi Mitra (Indian Institute of Information Technology, Guwahati): “Our Famines and their Famines: The Political Economy of Imperial Famines and Early Nationalism in Bengal”

Prof Pablo Mukherjee (University of Oxford): “Crow Meat, Crow Blood, Brown Feet: Afterlives of the Colonial Famine”

12.30: 13.00: Concluding Remarks

13.00-14.00: Lunch

Conference Ends.

Abstracts of Papers and Bio-notes of speakers:

1/ Prof Supriya Chaudhuri: “Witnessing Famine: Ethics, Representation, Art”

The 1943 Bengal famine constitutes a critical moment in the social and political history of the subcontinent, and it was also productive of a crisis of representation, whose nature we are yet to fully understand, in literature and the visual arts. For those whose task it was to bear witness, such as the photographer Sunil Janah, the artists Chittaprosad and Zainul Abedin, or contemporary writers such as Tarashankar, Manik and Bibhutibhusan Bandyopadhyay, Bijon Bhattacharya or Gopal Haldar, the distinction that Primo Levi makes between the witness and the survivor, testis and superstes, is acute: ‘we survivors are not the true witnesses: we are not only an exiguous but also an anomalous minority. Those who have not returned to tell about it or have returned mute, are the complete witnesses; we speak in their stead, by proxy.’ In my presentation, I want to look closely at a body of work produced in the year of the famine, 1943-44, or shortly afterwards, by writers and artists working from their own experience, asking how the moral crisis of representation, from the survivor’s perspective, is negotiated. I will discuss works like Tarashankar’s novel Manvantar (Famine, 1944) and Bijon Bhattacharya’s play Nabanna (New Harvest, 1944) where representation appears to fail, or to be deflected by partisan hope.

Bio:

Supriya Chaudhuri is Professor Emerita in the Department of English, Jadavpur University, and was educated at Presidency College, Calcutta, and at the University of Oxford, where she received her graduate and doctoral degrees. She has written and published in the fields of Renaissance studies, critical theory, Indian cultural history, urban studies, travel writing, sport, film, and modernism. Recent publications include the edited books Religion and the City in India (Routledge, 2022) and Commodities and Culture in the Colonial World (co-edited, Routledge, 2018), as well as articles in Études Épistémè, Thesis 11, Postcolonial Studies, Literature Compass, Open Library of Humanities, and Revue des Femmes Philosophes; and chapters in The Form of Ideology and the Ideology of Form (OBP, 2022), Machiavelli Then and Now: History, Politics, Literature (CUP, 2022), Recycling Virginia Woolf in Contemporary Art and Literature (Routledge, 2022), Asian Interventions in Global Shakespeare (Routledge, 2021), The Cambridge Companion to Rabindranath Tagore (CUP, 2020) and The Cambridge History of Travel Writing (CUP, 2019). She is active in debates on the humanities, urbanism, gender, education, and intellectual liberty in India.

2/ Dr Diya Gupta: “Hunger and the Homeland: Considering wartime photographs and letters on the 1943 Bengal Famine”

The 1943 Bengal Famine brings into focus features of turbulent life in 1940s India, as experienced on the home-front, and imagined and empathised with from international battlefronts. I will consider here photographs by communist journalist Sunil Janah, which urgently invite us to bear witness and make the catastrophic visible, and then move on to letters exchanged between Indian soldiers, stationed in the Middle East and North African fronts, and their loved ones. Reading these photographs and letter extracts alongside each other allows for fresh layers of meaning to emerge. How did Indian soldiers, fighting for the British, discover that there was widespread hunger in their homeland, despite the censorship of their letters? How did they conceive of the food they consumed as army rations while knowing that others at home remained hungry? In what ways does letter-writing become testimony when used by Indian civilians who did not themselves starve, but witnessed the ravages of famine? Through this comparatist approach, I trace the ways by which wartime communities of knowledge and bonds of empathy were being formed by contemporary audiences of both Janah’s photographs and Indian soldiers’ letters.

Bio:

Educated at Jadavpur University, Kolkata, as well as the University of Cambridge and King’s College London, Diya Gupta is a literary and cultural historian, and Lecturer in Public History at City, University of London. Formerly a ‘Past and Present’ Fellow at the Royal Historical Society and Institute of Historical Research, she takes multilingual approaches to life-writing, visual culture and literature, in relation to war. Her first book, India in the Second World War: An Emotional History (Hurst and Oxford University Press) was published in April 2023. See https://www.diyagupta.co.uk.

3/ Dr Janam Mukherjee: “Boom Time: Big Business and Famine in Bengal”

The Bengal famine of 1943, as has been argued by Amartya Sen, for one, was essentially a boom-time famine. Throughout the 1940s, in and around Calcutta, record profits were being made in war-time industries. On the cusp of war, Indian capitalists, in particular, were ideally placed to capitalize on Empire at war. It is during this period that Indian capital also rung the bell on European industrial interests, buying out European firms at record pace and commandeering the helm of war-time production, as well as national influence, in the process. The question of how these profits, and this influence, can be directly connected to the economic and market dislocations that underpinned famine in Bengal has not been widely studied. In this presentation I will trace the direct connections between the rapacity of industrial Calcutta and the starvation of Bengal. Throughout this period of extreme hardship for many millions, various chambers of commerce, as well as their constituent members, were empowered by colonial and military authorities to make bulk purchases in the province, write those purchases off against Excess Profits Tax (EPT), and transport food grains into Calcutta by means of special arrangements made in relation to wart-time policies. Industrial Calcutta was granted almost limitless powers to purchase in open markets, with little accounting of the size of purchases or the places of storage. The long history of speculation in commodity markets by an important sector of the business community in Calcutta raises further questions about market withholding, particularly after the Japanese bombings of the city in December, 1942. Procurement schemes in early 1943 were all embarked upon with the explicit aim of shifting rice from the countryside, and into the warehouses of industrial Calcutta, and a census in the spring of 1943 to asses the “food position” of the province, conspicuously excluded Calcutta, where it was well understood significant stockpiles were being hoarded. Meanwhile, the economic situation in India at large was being further undermined by the accrual of a massive IOU in the form of “sterling balances” being held in London against war expenditures in India. By 1944, the Federated Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) were claiming these sterling balances as their own in the Bombay Plan, even while Bengal continued to starve. By the end of the war the dominance of Indian capital lent it inordinate influence in shaping plans for a transfer of power in the short and volatile years to come. In short, I will be looking to analyze the extent to which the economic and political influence of India’s big business houses was built in direct relation to the mass disempowerment and starvation of Bengal during World War Two.

Bio:

Janam Mukherjee is an Associate Professor of History at Ryerson University in Toronto, Canada. He holds a PhD in Anthropology and History from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Dr. Mukherjee’s book Hungry Bengal: War, Famine, Riots and the End of Empire incorporates extensive archival and oral history research to draw structural links between war, famine, social upheaval and civil violence in mid-twentieth century Bengal. Mukherjee is also an anti-war activist, musician and creative writer.

4/ Dr Benjamin Siegel: “Bengal, Revisited? India’s 1951 Food Crisis and the Postcolonial Quest for Indian Self-Reliance”

In 1951, not even a decade past the ravages of the Bengal Famine, the specter of widespread shortages across India threw nationalist leadership’s claims to moral authority into stark doubt. Over a precarious year, imports paid for by scarce reserves of foreign aid averted greater crisis. Yet observers in the press were relentless on free India’s leadership, likening the crisis of 1951 and eroding many of the claims the Congress party had made around the just provision of foodstuffs. This paper examines the interlinked relationship between the Bengal Famine and the shortages of 1951, a crisis that has been all but entirely absent from popular and scholarly accounts of the early years of India’s independence. Drawing on popular accounts of the famine, this paper reveals the significance of 1951 in India’s struggle for food and post-colonial self-determination, exploring how it illustrates the meaning of “self-reliance” and the fear of failure, how it widened the scope of engagement with India’s food problem to a global scale, and how it set the stage for later debates of the 1950s and 1960s.

Bio:

Benjamin Siegel is a historian of modern economic life and politics, agriculture, and the environment, with a geographic focus on South Asia and its entanglements with the wider world. His first book, Hungry Nation: Food, Famine, and the Making of Modern India (Cambridge University Press, 2018), interrogated the ways in which questions of food and scarcity structured Indian citizens’ understanding of welfare and citizenship since independence. Professor Siegel’s current book project, Hooked: A Transnational History of the United States Opioid Crisis, is under contract with Oxford University Press. He is working on three interlinked future projects: a short history of tangible and intangible resources in modern India, a global history of South Asian development, and a project on traffic, roads, and automobiles in the region.

5/ Joanna Simonow: “Transnational Famine Relief and Anti-Colonial Politics on the Eve of Independence”

One might think that the response of aid providers and fundraisers to the famine in Bengal rightly takes a back seat in the history of the famine. The negligence and complicity of the British government, the American-led international aid community and Indian elites who did too little, too late to prevent the deaths of millions of Bengalis is well documented. As to the many local and more distant non-governmental relief providers and fundraising committees, lack of resources and political influence crippled their assistance; Bengal’s needs far outstripped their capacity. Despite their marginal place within histories of the Bengal famine, it is these numerous small-scale efforts undertaken to counter the humanitarian tragedy unfolding in the Indian province that this paper investigates. I suggest that such a study embeds the Bengal famine more firmly into the history of South Asian decolonisation, as well as pushes the geographical boundaries that commonly frame studies of the famine.

News about the famine moved through personal and organisational contacts, first alerting the South Asian diaspora and Indian political organisations, before the famine was reported in the Indian national and international press. In the months that followed, the geographical reach became wider and the political background of those in favour of famine relief more diverse. Mobilising aid and raising public awareness of the famine served political groups outside India to express support for Indian nationalism (and for a very specific political and social group on this political spectrum). In India, the United States and Britain, the political context of the Second World War hindered public criticism of British imperialism. Famine relief became a means for political parties and interest groups to reach out to the Indian elite and demonstrate their political endorsement. Mitigating starvation in Bengal also served Indian organisations and individuals to advocate and protect the interests of particular social groups. Since famine relief operated through different political frames, it can be used as a burning glass for the political arena of Bengal and wider India, and for the international contacts of Indian political groups on the eve of independence.

Bio

Joanna Simonow (she/her) is Assistant Professor in the Department of History of the South Asia Institute in Heidelberg. Her work on famine relief, nutrition and food politics has been published in South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, Zeithistorische Forschungen and the Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. Her book Ending Famine in India: A Transnational History of Food Aid and Development, c. 1890–1950 is forthcoming with Leiden University Press in June 2023. Her current research explores the sexual and private histories of Indian anticolonialism and South Asian diaspora formation in Europe.

6/ Dr Abhijit Sarkar

TBA

7/ Urvi Khaitan: “‘My Body Costs Five Hundred Rupees’: Women’s Work in War and Famine”

Despite the significant corpus of existing work on the Bengal Famine, its gendered effects remain understudied. This paper focuses on the women made destitute by the Famine and how they coped with this impoverishment, mounting survival strategies through their engagement with the labour market. The image of starving mother and child was ubiquitous in contemporary accounts and depictions of the Famine—in general, women have been conceived of as passive victims, driven to prostitution out of crippling hunger. Such a unidimensional and reductive approach to women’s experiences of the Famine is problematic for at least three reasons. One, it ignores a longer-term history of complex and multi-sectoral women’s labour market activity in Bengal. Two, the idea that women were left helpless after their husbands or other male earners abandoned them denies independent economic agency to women, who also lost their livelihoods and resources. Three, while saying that women took to selling sex because of starvation is not incorrect, it is an oversimplification that does not sufficiently address the absence of choice in such a labour market. The mechanisms by which that choice was circumscribed or taken away altogether from women have not been analysed.

A mixed-methods approach bringing together qualitative archival material, quantitative data, photographs, and oral histories makes it possible to reconstruct a history of women’s work as they navigated an economy marked by extreme constraint and asymmetries of power. Gendering Famine data shows that even while more men than women died, women were disproportionately displaced in comparison to men. When put in conversation with stories of individual displacement, distinct women’s histories of the Famine emerge. Women adopted multi-pronged strategies of survival and wartime labour was one of a limited range of opportunities available to them. In their tens of thousands, they joined the military Labour Corps, building the roads and runways that would form the foundation of the Allied war effort in South Asia. Many of these women also worked in prostitution to supplement their earnings or as their chief source of income, or were trafficked into the sex trade. On the one hand, this generated panic among Indian social and political activists about what they saw as a moral collapse. On the other hand, venereal disease was a major source of anxiety for military commands.

The bodies of labouring women became sites for panics and anxieties about interracial encounters that undercut hierarchies and pushed against social barriers. Responses to their labour were in general condemnatory, patronising, and moralising. Notwithstanding this elitist discourse, the women who peopled the Corps or worked in prostitution were economic agents who, operating in highly circumscribed contexts, were actively making decisions about survival, work, and the family. They were individual providers of labour power and were key actors in a global wartime economy with extensive transnational links. They were not simply passive recipients of charity, but actively looked for strategies to subsist and make do—whether it was through relief kitchens or other charitable organisations, manual labour, prostitution, or all of these combined—while they bore a disproportionate burden of an increasingly extractive and command-based economy.

Bio:

Urvi Khaitan is a final-year doctoral student in History at the University of Oxford. Her thesis on women and work in the Indian economy analyses the ways in which women pushed to the margins of colonial society engaged with paid work. Taking the 1940s—a period of war and famine—as lens, the thesis takes a case-study approach to investigate women’s work across formal and informal economies. She has published an article on colonial India’s ‘women beneath the surface’—the tens of thousands of women who worked in coal mines while battling a cost-of-living crisis and starvation during the Bengal Famine and Second World War.

8/ Dr Sona Datta:”From the academic to the actual: How hunger is still used as an instrument of violence against the body”

What can remembering past hunger through the medium of contemporary cultural production tell us about the cultural politics and aesthetics of food in the present? The 1943 Bengal Famine was a direct consequence of colonial resource extraction, hoarding and unchecked inflation. Rice harvests that had sustained local populations for millennia were appropriated by the British for the war effort, making no provision for the Bengalis’ survival needs. This manufactured famine has echoed down through the years in an image of a region unable to provide or care for itself implicating the memory of three national narratives.

Our aim is to use art to create a site of interrogation with this crisis of the past and find in the act of remembrance fresh resonances with food crises in our own times. In collaboration with NPO Poet in the City we are facilitating artists to collaboratively interrogate their creative

endeavour around the central idea, leading to public art commissions in the UK, India and

Bangladesh through 2023-5.

This project provides evidence for academic and public reappraisal in the context of decolonisation, responding effectively to modern British audiences today and to the UK’s standing in dynamic research and groundbreaking creative economies.

Bio:

Sona Datta is a freelance curator, writer and broadcaster. She was previously Head of South Asian art at the Peabody Essex Museum in Massachusetts where she extended the world-renowned 20th C Indian art collections to include the best contemporary art referencing all of South Asia.

Prior to the PEM, Sona worked at the British Museum for 8 years where her exhibitions included the flagship Voices of Bengal season (2006), which attracted more people of South Asian extraction than any project in the British Museum’s history. Sona also radically redefined the British Museum’s engagement with modern collecting through the acquisition of contemporary art from Pakistan that linked to the Museum’s rich holdings of historic Indian painting. In 2015 she wrote and presented the BBC4 series Treasures of the Indus now broadcast to a global audience of >90m. In 2019, she curated She Persists at the 58th Venice Biennale, showcasing the work of three generations of trailblazing female artists from as many continents including, Judy Chicago, Lynda Benglis, The Guerilla Girls, Mithu Sen, Rose McGowan and others.

Her new book is a radical revision of Indian art, which will reset the lens on the so-called ‘East’. She lives in London with her husband, two boys (and no dog). As a writer she is represented by David Godwin Associates.

9/ Dr Anuparna Mukherjee: “The Famished City: Displacement and the Trails of Hunger in Calcutta of the 1940s”

My paper explores the affective contours of Calcutta’s modernity—the former capital of the British Empire in India in the decade of 1940s through a trail of catastrophes— World War II, the famine and the Partition. To locate the fraught transition of the city and its neighbourhoods in the last years of British rule, the paper specifically evokes the sensory landscape through food, disease and the intrusion of jarring sounds that pervaded the urban life against the specific context of the ravages of war and the famine. The paper further delves into the accelerated and chaotic human movements, destitution and hunger through “sensory displacements” and their impact on the urban subjects, altering the perceptions of the quotidian. The paper brings together a constellation of works from the paintings and illustrations of Somnath Hore, Chittaprosad and Zainul Abedin to the plays and poems of the Inter-War writers, who brought forth new and radical ways of apprehending the sensorial reality of the urban and the modern, informed by the history of colonial subjugation. Against the locally configured history of the Bengal famine and mass starvation, these works are particularly preoccupied with the emaciated and hungry body—as the conduit of “mediation” between art, community and social relations. They depict the body at its breaking points through disease, malnourishment and continuous assault on the senses. By engaging with their aesthetics this paper, thus, reads “hunger” as a recurrent trope that redefined the understanding of the modern urban space.

Bio:

Anuparna Mukherjee is an Assistant Professor of Literature, at the Department of HSS, IISER Bhopal. She holds a PhD in Literature from the Australian National University (ANU), Canberra. Her research interests include memory studies, cities and neighbourhoods, and colonial modernity. Her recent publications include “viral nostalgia” in EPW and “Knots of Time Reading Nostalgia in Bengali Literature from 13th to the 19 Century” in the anthology, Retelling Time: Alternative Temporalities from Premodern South Asia by Routledge. Her essay on “waste and spectrality” is included in the anthology on Nabarun Bhattacharya by Bloomsbury. Her latest writing, “Imperial

Malady: Empire and Affect in Colonial Narratives” in Ecological Entanglements: Affect, Embodiment and Ethics of Care, has been published by Orient Blackswan.

10/ Dr Binayak Bhattacharya: The 1943 Bengal Famine and Cinema of the Left, circa 1940s

The paper attempts to network the cinematic modes of addresses through which the left-wing cultural movement in India attempted to produce a creative response to Bengal Famine of 1943. Although the cinemas of India started responding to the issues of food crisis and hunger since the early 1940s (Roti, 1942), the Bengal famine of 1943 appeared a completely different experience for the artists of that time. Films made during the famine, notwithstanding the censorship, were relatively silent, with only passing references about the crisis (Udayer Pathe, 1944). Indian People’s Theatre Association’s (IPTA) Dharti Ke Lal (Children of the Earth, 1946), on the contrary, was the first and most prominent cinematic works during that era which expansively portrayed the Bengal famine and its impact on a broader social canvas. A loose adaptation of the landmark Bengali play Nabanna (The Harvest, 1943), also staged by the IPTA artists, the film narrates the plight of a village family during famine. Visual representation of famine that Dharti Ke Lal established, however, has a larger history. It accommodated a whole range of creative responses from literature, visual arts, theatre, music, journalism and photography within its formal structure to develop a new representative feature of famine and hunger. Such responses emerged mostly from the creative attempts led by the leftwing intellectuals. Most of the artists and activists from the leftist collective opted for a formal improvisation, as the available modes were hardly adequate to realise and express the depth and gravity of the famine. In addition to that, a sense of documentary realism, relatively unfamiliar to the available cinematic modes of that era, also found its space in Dharti Ke Lal. The paper traces such processes in leftwing cultural movement that did not only create new instances in Dharti Ke Lal, but gave birth to a political iconography of famine and hunger in Indian cinema for the years to come.

Bio: TBA

11/ Prof Vinita Damodaran: “Climate Signals Droughts, Floods and Famines in South Asia”

TBA

12/ Dr Rajarshi Mitra: “Our Famines and their Famines: The Political Economy of Imperial Famines and Early Nationalism in Bengal”

We have schooled ourselves to draw a line of demarcation between Indian famines and European ones. The former are gigantic calamities while the latter are Lilliputian distresses.

- The Bengal Magazine (1881), Vol 9, pp 333 – 334.

In the two decades between 1860 and 1880 British India was hit by nearly five severe famines. Early Indian nationalists used comparative approaches to analyze the causes behind these famines and had put together a coherent critique of the British Empire’s malicious economic policies. The literary culture in Bengal had responded in metaphors, allegories and narratives as economic nationalists were forming their theories about the drain of wealth from imperial peripheries to fatten its centre. This paper looks at two writers – W W Hunter (1840 – 1900) and Lal Behari Dey (1824 – 1892) – who responded to British Empire’s famine policies in their writings. Several years before the first Famine Commission (1880) published ‘scales’ to measure famine, W W Hunter, a Scottish historian and a civil servant in India, wrote treatises on famine policy and was keen on establishing a famine system. Hunter’s famine system was more anthropological in nature. He was bent on establishing a cultural archive to fathom the causes behind famines in the Indian province of Bengal. Reverend Lal Behari Dey, a celebrated Bengali convert to Christianity, was a minister of the Free Church of Scotland in India. As an editor of The Bengal Magazine, Reverend Dey commissioned articles on famines in India. In his Bengal Peasant Life (1874) and Folk Tales of Bengal (1875), he created allegories on monstrous hunger and equally monstrous governance. In this paper, I look at how Hunter’s famine system becomes the colonial narrative that Reverend Dey desires and dreads. He builds a phantasmagoria of famine tragedies that flesh out Hunter’s reports of cannibalism and other untold horrors during the famines.

Bio:

Dr Rajarshi Mitra is Assistant Professor in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Information Technology, Guwahati. Before joining IIIT Guwahati, he was Assistant Professor in Department of English, Central University of Karnataka. He has an M Phil (2010) from the Department of English, University of Hyderabad and a PhD (2014) from the Department of English Literature, The English & Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad. For his PhD, he had worked on natural history narratives from India between 1857 and 1950, and his M Phil was on colonial tiger hunting narratives. His research interests include history of cinema and various cultural experiences of the British Empire. He has published papers on the Bengali experience of the First World War, famine rhetoric in British India, cinema propaganda in colonial India and the big game hunting culture of the Raj era. In IIITG, he teaches Anglo-American Science Fiction, Introduction to Film Studies and Indian Writing in English.

13/ Prof Pablo Mukherjee: “Crow Meat, Crow Blood, Brown Feet: Afterlives of the Colonial Famine”

TBA

The British Empire and Colonial Famines: History, Culture, Critique

Second Conference

Indian Institute of Information Technology Guwahati

January 7- 8, 2023

Saturday, Jan 7

9.00am – 9.15am: Registration

9.15am – 9.30am: Welcome (Dr Rajarshi Mitra, Dr Sourit Bhattacharya, and Dr Binayak Bhattacharya)

9.30am – 11.00am: Panel 1: Famine in India – Debates and Discourses (Chair: Prof Sachidananda Mohanty ) Venue: Board Room

- Prof Arup Maharatna (Central University of Allahabad): “Famine Mortality, Epidemics, and Relief Policy – Major Colonial Famines in British India”

- Prof Sanjay Kumar Sharma (Ambedkar University): “‘Profit vs Profiteering: Negotiating Laissez Faire during Famines in Colonial India”

- Dr Srimanjari (Miranda House, University of Delhi): “Famines and Society”

11.00am- 11.15am: Break

11.15am – 12.45pm: Panel 2: Famine Regions – Odisha and Bengal (Chair: Dr Peter Schmitthenner ) Venue: Board Room

- Prof Bidyut Mohanty (Institute of Social Sciences, Delhi): “Deep Social Impact of Famines: Emergence of a Chhatrakhia Community and the Orissa Famine of 1866.”

- Prof Sachidananda Mohanty (Former Vice-Chancellor, Central University of Odisha): “The Odisha Famine of 1866 and the Birth of a New Province”

- Dr Tirthankar Ghosh (Kazi Nazrul University): “Disaster, Ecology and State: A Cyclonic Approach to Famines of Colonial Bengal”

12.45pm – 2.15pm: Lunch

2.15pm – 3.45pm: Parallel Sessions: Panels 3 & 4: Bengal Famine

Panel 3 Bengal Famine: Memories of Hunger (Chair: Dr Dhurjjati Sarma) Venue: Board Room

- Deepawali Mitra (Jadavpur University): “Remembering the 1943 Bengal Famine through Children’s Literature”

- Shireen Sardar (Jadavpur University): “Remembering Chiyattorer Monontor (Bengal Famine of 1769-70) – Politics of Colonial Crisis”

- Srijita Biswas (IISER Bhopal): “Writing Memory of Hunger: In Search of ‘Astonishing Smell of Rice”

Panel 4 Bengal Famine: History and Politics (Chair: Dr Trina Nileena Banerjee)

Venue: Conference Room

- Subhasis Pan (Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University): “Look Back to Hunger: The British Empire and the Bengal Famines in the Nineteenth Century India”

- Reeti Basu (Jawaharlal Nehru University): “War, Famine and Foreign Soldiers”

- Dr Ranu Roychoudhury (Ahmedabad University): “Bearing Witness to Mid-Twentieth Century Hunger in India” online

3.45pm – 4.00pm: Break

- 4pm – 5.30pm: Parallel Sessions: Panels 5 & 6 (Chair: Dr Srimanjari )

Panel 5: The Famished Body: Visual Culture and Famine Venue: Board Room

- Seng Ong (University of Cambridge): “The Famine Pastoral: Colonial Famine and Western Visual Culture” online

- Sumantra Baral (Jadavpur University): “The Artist as Reporter: 1943 Bengal Famine and Inception of Visual Reportage in Colonial Bengal”

- Attrita Goswami (University of Burdwan): “The Famine in the Frame: Studying Visual Representations of the Famished Body in India and Ireland”

Panel 6: Various Famines (Chair: Dr Sourit Bhattacharya)

Venue: Conference Room

- Dr Dhurjjati Sarma (Gauhati University): “The Mizo Famine of 1959–60 and the Assamese Response”

- Nilanjana Chatterjee (Durgapur Government College): “Indigenous Naga Famine”

- Upal Chakrabarti (Presidency University): “Sites of Death as Fields of Labor and Improvement: Famine Relief in British India” online

5.30pm: Close of Day 1

7.00pm: Conference Dinner

———————————————-

Sunday, Jan 8

9.00am – 10.30am: Panel 7: Famines – Moral Responses (Chair: Prof Sanjay K Sharma)

Venue: Board Room

- Dr Tanuja Kothiyal (Ambedkar University): “The Moral Economy of Distress: Famine and Negotiations in the Thar Desert in the 18th and 19th Centuries”

- Dr Trina Nileena Banerjee (CSSSCAL): “Scenes from the Famine: Chittoprasad, the IPTA and the Art of Visual Reportage”

- Dr Peter Schmitthenner (Virginia Tech): “Water on the Brain”: Arthur T. Cotton and Debates about Famine in Late 19th Century India”

10.30am – 10.45am: Break

10.45am – 12.15pm: Panels 8 & 9

Panel 8: Famine, Migration and Imperial Response (Chair: Dr Tanuja Kothiyal)

Venue: Board Room

- Sagarika Naik (Princeton University): “Famine, Empire and Migration in South Asia.”

- Ayan Das (Vidyasagar University): “‘Famine, Migration, and Demographic Change: Analysis of Relation between Famine of the Chota Nagpur and Demographic Change in the Brahmaputra Valley under the Colonial Regime.”

- Dr D Sathya (K L University): “Imperial Railways and Alleviation of Famine Distress in Colonial South India (Special Reference to The Great Famine of 1876-78)” online

Panel 9: Famine: Representation and Beyond (Chair: Dr Binayak Bhattacharya)

Venue: Conference Room

- Dr Avishek Ray (National Institute of Technology Silchar): “Testimonial Evidentialism and (Anti-)Colonial Aesthetics Documenting the 1943 Bengal Famine”

- Dr Jati Shankar Mondal (Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University): “Colonial Brutality, Artistic Sensibility and Cultural Codes: Reinterrogating (the Fall of) Empire through Famine Sketches of Bengal Famine (1943) and related writings”

- Dr Umasankar Patra (National Institute of Technology, Tiruchirappalli): “Hunger, Precarity, and Belonging: Reading Ananta Das’ Representation of Famine in Odisha”

12.45pm – 2.15pm: Lunch

2.15pm – 3.45pm: Panels 10 & 11

Panel 10: Famine Region: South India (Chair: Dr Rajarshi Mitra)

Venue: Board Room

- Rahul Vijayan & Prof Nagendra Kumar (IIT Roorkee): “Revisiting the Madras Famine: The Politics of Caste, Hunger and Protests”

- Dr C Chandra Sekhar (SRR & CVR Government Degree College, Vijayawada): “Burning Hunger: The Great Famine, Caste Differences and Missionary Christianity in Colonial India” online

- Swathilekha Thampy (Kannur University): “Analysis of Famine of Travancore Princely State; 1860 to 1878”

Panel 11: Bengal Famine: Revisited (Chair: Dr Avishek Ray)

Venue: Conference Room

- Sourapravo Chatterjee (University of Calcutta): “Framing Famine: A Socio-Semiotic Analysis of Mrinal Sen’s Akaler Sandhane”

- Dr Dipanjan Ghosh (Nabadwip Vidyasagar College): “The Politics of the Great Bengal Famine through the Lens of the Famine Trilogy of Gopal Halder”

- Aryama Bej (Jadavpur University): “Spectacle of ‘Hunger’: Socio-Realist Dance in 1943 Bengal Famine”

03.45pm – 4.30 pm: Conference Feedback – Roundtable Venue: Board Room

4.30 pm – Vote of Thanks

4.45 pm – End of Conference

—————————–xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx————————————

Conference Abstracts:

RSE Research Network

“The British Empire, Scotland, and Indian Famines”

Second Conference

The British Empire and Colonial Famines: History, Culture, Critique

Indian Institute of Information Technology, Guwahati

January 7- 8, 2023

DAY ONE: SATURDAY, JANUARY 7, 2023

9.30 am – 11.00 am

Panel 1: Famine in India – Debates and Discourses

Chair: Prof. Sachidananda Mohanty

Venue: Board Room

Prof. Arup Maharatna (Central University of Allahabad)

“Famine Mortality, Epidemics, and Relief Policy – Major Colonial Famines in British India”

As famines generally turn calamitous at least in its immediate/short run consequences, it often gives rise to debates and controversy over its exact causation and accountability. Those in power or at the helm of ruling and administering a polity have perennially evinced a tendency to portray and posit famines as a natural disaster rather than anything else. This tendency is perhaps nowhere more glaring than in the official reports and documents produced by the British colonial administration in India’s historical context of many major famines that occurred in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The colonial affinity of positing famines and its catastrophic consequences squarely as an unintended outcome of nature’s unpredictable/unavoidable fury has not only not died down in the post-colonial period, but its supportive argumentations and rationalizations of late have acquired much academic and intellectual sophistications in echoing the old colonial ‘alibis’ for large-scale acute hunger, starvation and millions of excess human deaths caused directly by various epidemics that used to ensue following mostly those drought-induced historical famines across India.

For example, there is an ongoing debate as to whether the famine-induced epidemics – the proximate recorded causes of the bulk of excess deaths – can be attributed directly to famine-caused food shortage, starvation, and acute nutritional deprivation as such or to social, climatic, and other inevitable disruptions including population movements and excessive crowding in relief camps, which produce influences on mortality apparently/admittedly independent of those caused by famine and food shortage per se. My proposed paper would seek to throw new/additional light on my earlier contribution to this debate. More specifically, I propose to reinforce my earlier position, namely, that excess mortality due proximately to the outbreak of various epidemics cannot be seen to be dissociated or distinct from excess mortality caused directly by famines commonly defined in terms of distress, mass hunger, starvation, and nutritional debilitation.

Prof. Sanjay Kumar Sharma (Ambedkar University, Delhi)

“Profit vs Profiteering: Negotiating Laissez Faire during Famines in Colonial India”

The expansion of British rule in early nineteenth century India was marked by a number of famines that brought about decisive shifts in relief policies that were shaped in the context of new notions of political economy and state responsibility. This paper analyses evidence drawn from some instances of famines in north India on the specific issues of profit and profiteering during dearth marked by price rise and hoarding. The attempts by British officials to promote the tenets of free trade and non-interference in the market considered good for the economy posed dilemmas during subsistence crises when food prices rose beyond popular expectations. Such situations were often aggravated due to hoarding by grain dealers who withheld supplies to the market expecting windfall gains. In this they were aided by the reluctance of colonial officials to interfere in the market to regulate prices as official British policies were driven by prevailing notions of political economy that favoured laissez faire. However, they were met with indigenous responses that regarded profit-seeking in times of famines as illegitimate profiteering. There were numerous instances of plunder of grain and violence against landlords and traders dealing in grain during famines in British India. Studies of their pattern indicate that violence was often selective as generally the targets of ire were those who were perceived as taking undue advantage of shortages and price rise. There were popular expectations from colonial administrators to intervene in the market to ensure supplies and sale of food at ‘just’ prices. This produced ambivalences in the colonial bureaucracy committed to the doctrine of laissez faire as local officials grappled with a starving populace reeling under high prices often due to hoarding and ‘illegitimate’ profiteering. This paper analyses some select narratives produced in colonial north India dealing with such issues during situations of dearth. It analyses official debates on the desirability of administrative intervention to regulate high prices, the opinions of the English press and texts produced by members of emerging indigenous middle class in north India. Based on these, the paper will attempt to explore the complex ways in which the officially sanctioned theoretical doctrine of laissez faire operated in practice and was negotiated by the functionaries of the colonial regime and its subjects during subsistence crises.

Dr. Srimanjari (Miranda House, University of Delhi)

“Famines and Society”

Both war and famine evoke images of stark finality. When we think of these two ‘events’, we relate them with rampant death and devastation. The two events may occur independent of each other at different periods of time but when they occur one after the other as cause and effect, the impact is doubly devastating. In the colonial situation in India, when the state equipped itself with absolute powers during World War II, the impact of the two crisis situations unfolded in extremely complex ways in Bengal.

While the situation of constant hunger was not unknown in several parts of Bengal, the extent of it and the millions of lives that it affected in multiple ways during the famine of 1939-1945 was unprecedented. During this crucial period, while the Bengal countryside was slow to change, the towns and cities, particularly the city of Calcutta witnessed far-reaching transformations.

The city had beckoned many kinds of opportunity seekers. This paper intends to show how the famine and day-to-day life during the famine affected different sections of society. The famine prompted writers, photographers, painters and researchers to travel and collect data and information which in normal course of time may not have caught their attention. When we tap these and other kinds of literature, which some refer to as ‘peddler literature’, we are able to visualise how persistent hunger moulds senses and sensibilities.

11.15 am – 12.45 pm

Panel 2: Famine Regions – Odisha and Bengal

Chair: Dr. Peter Schmitthenner

Venue: Board Room

Prof Bidyut Mohanty (Institute of Social Sciences, Delhi)

“Deep Social Impact of Famines: Emergence of a Chhatrakhia Community and the Orissa Famine of 1866.”

All the great famines have produced serious consequences in the social, economic and political spheres. Unavailability of food, with loss of purchasing power impacts society as a whole. In fact, role of food in the history of humanity determines the nature of the cultural processes in the development of the ethnic and regional identity as well as political formations. It is true that societal response tries to minimize these effects by assimilating some of the impacts over time but the scars are so deep that it takes generations to erase it, and that too rarely completely.

Thus, in studying famines, economic statistics on failure of crops, extent of rainfall, number and categories of dead and sick, migrants and malnourished and so much else is no doubt important for capturing the magnitude of the famine. But it is equally significant to grasp the social and cultural experience of the people and the processes which were unleashed by natural calamity and policy measures before, during and after the famine. These may only be partly gathered from the government documents. One has to go into many other kinds of sources, non-official documentation, literary writings, study of related institutions, social practices, folk tales and sources of memory, among others. Only then can one capture the comprehensive picture of the historical catastrophe.

We have examples such as the famous painting by Van Gogh, Potato Eaters which is a permanent reminder of the Irish Famine of 1845-49 and its manifold consequences encrypted in people’s psyche even today. Studies of impact of the 1874 and other famines on castes in Bihar, especially on the Kurmi community show the far-reaching effects of the famine period on the life of people. The widespread effects of the Bengal Famine of 1943 on the social process, political behavior, literature, arts and films, besides state policy, are well-documented. Similarly, I wish to take up the case of the emergence of the Chhatrakhia Community an important impact of the great Orissa famine of 1866 and its presence to this day in Orissa. This was one of the many currents triggered by the famine which had long term impact on every aspect of life and society in Orissa . In my recent book, A Haunting Tragedy: Gender, Caste and Class in the 1866 Famine of Orissa I have not only gone into the economic aspects using available statistical data, but also examined the social consequences in some detail. One aspect, namely the emergence of the Chhatrakhia community dealt there, I would like to further examine and make an argument about the operation of caste-class dynamics in relation to economic, social and political power. This has some relevance to the contemporary times.

Due to deficit rainfall in 1865 and excessive rains in 1866 and the faulty grain export policy of the British government among other factors, like poverty the highly stratified society of Orissa suffered from severe food shortage and famine in 1866 leading to the death of an estimated one million people, nearly one third of the population of the Orissa division. During the famine various agencies of government, private companies, missionaries, temples and charitable organisations set up relief centres to feed the starving poor. Absolute shortage compelled people of poorer community as well as relatively poorer farmers, especially people from the lower, servicing castes among them vast number of Dalits, came to the relief centers in large scale. Very often the supply of food in the relief centres was far less than the demand. The managers of the relief centers tried to control the situation by adopting different kinds of measures and sometimes drove away many needy relief seekers particularly women and small children. Many were left to die in harness. The official reports as well as local press were full of those descriptions reporting on the torturing of the crowd, quality of the food, living conditions and so on.

When conditions became slightly normal and people started returning to their villages, they were branded as people who had eaten in Chhara or public relief centres. Since they ate along with people from various castes and ate food cooked by people not belonging to their own castes, they were accused of violating their caste norms. Since most of the big relief centres were run by government or the Christian missionaries or a British Company like the East India Irrigation Company they had lost the supposed ‘purity’ of their caste. The branding was mostly done on the initiative of the upper caste landlords and priests and the big zamindars. As the number of such people swelled the group was identified as Chhatrakhia (those who ate in relief centres).

Three distinct features should be noticed in case of such people. First, they originally came from a number of different castes, though the bulk of them were from the chasha (farming caste) and service castes or Dalits. Undoubtedly there were also some from poor sections of the middle and upper castes. Second, many of them not only ate at the centres, but also got exposed to missionary preaching. In the process some adopted Christianity, their children and orphans stayed on and joined schools. Some settlements came up consisting of Christian households. Third, they married among themselves – though maintaining caste hierarchy among themselves. Over time many clusters of chhatrakhia habitats sprang up in different areas. Many of them joined construction work as daily wagers and other petty jobs such as selling vegetables in urban areas and canal side strips. In such circumstances some young women also engaged in sex work. Thus, during the famine period, the interplay of caste, religion, occupation and actual livelihood challenges produced new socio-economic formations in the emerging political economy shaped directly or indirectly by the state and the powerful social forces during the colonial era. The new caste-class experience that subverted the prevailing norms was unacceptable to the established elite and the colonial state acquiesced with it.

That the Chhatrakhias were a deprived section of society was recognized by the social reformers who appealed to the government, Brahmin Pundits in big temples and also to the zaminadars to take back these people to their village community and readmit them to their original castes. Except for stray cases, this effort fell flat.

While reading those reports on the relief work one always remembers the experience of Irish Famine where dreaded Typhus epidemic decimated the relief seekers in large scale. In Orissa cholera and fever took a very heavy toll. The vivid descriptions of the sufferings stirred the consciousness of the intellectuals then and even now. The writers, politicians and playwrights produced much creative and soul-stirring literature. Oriya nationalism grew out of this process demanding recognition of Odia identity and formation of a separate province of Orissa. Radical consciousness was manifest in several writings which showed how famine victims such as Sanatan became rebels calling for overthrow of the colonial regime and got transported to Kalapaani.

An interesting set of cultural developments was in the realm of religion. Some of the members of relief seekers became Christians. Some of the members of the Chhatrakhia community became the followers Mahima Dharam, a rising movement against idol worship and Brhminism while many others joined the Brahmo Samaj. All new converts had an eclectic orientation respecting the prevailing Hindu practices continuing the syncretic tradition of Vaishnavism and Sufism in Orissa.

In Orissa’s language and culture the famine’s imprint remained in the use of many terms such as Na’ankia referring to the hungry and starving, chhatrakhia as an abuse for violator of social norms and many others. The cuisine of the Oriya people changed drastically with many new recipes from the scarcity period entering the kitchen. That they were still struggling to overcome the scar of the famine from the Odia psyche was evident whenever the famine conditions of Kalahandi or Nagada come to the public discourse.

I may add that not all this could be discerned only from the government records. Besides the study of the press and a large body of literature, one had to interview chhatrakhias in their habitats and follow their activities over a period of time to be able to construct this story.

In 2016, during the 150th year of the Orissa Famine of 1866 many issues were debated reflecting diverse vantage points demonstrating the continuing interplay of the caste-class, religion and politics. Now as Orissa prepares to celebrate the centenary of the formation of the linguistic province in 2036 these issues are likely to acquire even more salience as the elite wish to forget the scar of the Great Famine and build a prosperous state. Chhtrakhias of today should be a stark reminder to this history where many old problems of poverty, malnutrition, distress migration caste, class and gender inequities still persist in today’s Orissa. The challenge of that history has to be met.

Prof. Sachidananda Mohanty (Former Vice-Chancellor, Central University of Odisha)

“The Odisha Famine of 1866 and the Birth of a New Province”

During the famine, a correspondent had said that henceforth there would be no problem to fill in the pages of the newspapers. For, there would be a surfeit of news regarding flood and famine.

Utkal Dipika , 4 Sept. 1869

The epigraph above sums up the nightmare of all editors: how to fill up the pages of a periodical week after week? Such anxieties, unknown hitherto to a primarily agrarian social order in colonial India, would become increasingly dominant in a knowledge society, governed by the desire for information literacy. And yet, as events were to prove soon, the claims of the anonymous correspondent of Utkal Dipika would be superseded by the demands of the colonial subjects for a distinct cultural identity for a separate province called Orissa in 1936.

Begun primarily as a popular medium for discussion and dissemination of news related to the devastating Odisha Famine of 1866, Utkal Dipika soon outgrew its primary objective and became a carrier and compendium of news and views from far and near that few newspaper-periodicals of the region could surpass then and now. Further, from the beginning till the death of its founder, the journal championed the linguistic, cultural and economic interests of the Odias. It spearheaded a powerful regional cultural movement.

Based on archival research, this talk would explore the interface between Famine Studies and identity formations in Colonial India. It will chronicle the fascinating manner in which the Victorian Periodical Press arose in Eastern India against the larger backdrop of the Great Odisha Famine of 1866.

Dr. Tirthankar Ghosh (Kazi Nazrul University)

“Disaster, Ecology and State: A Cyclonic Approach to Famines of Colonial Bengal”

The present study intends to examine Bengal famines in the backdrop of cyclones which occurred in colonial Bengal since the second half of the nineteenth century. I would argue that famine can be also studied in relation with other natural disasters, such as cyclones. Although famine studies have emerged as a distinctive discipline within the broader spectrum of environmental history, famines in colonial India or Bengal still deserve adequate historical investigation from the perspective of history of natural disasters. Hence, the present study intends to offer a cyclonic analysis of famines of colonial Bengal. The famines of 1866 (Bengal-Orissa Famine), 1873-74 (Bihar-Bengal Famine), 1896-97 and the 1942 (the Great Bengal Famine) can be re-examined with their extended connection with the cyclones which had taken place in Bengal in 1867, 1874, 1897 and 1942 respectively. The famine-period which was marked by deficiency of rainfall and widespread crop failure had witnessed sudden increase in rainfall and floods as a result of cyclonic visitation that further caused severe destruction of human lives, cattle and commodities. Hence, the two extreme weather events had not only aggravated vulnerability of the poor, they further intensified the crisis which was already caused by hunger, homelessness and death. The cyclones, by killing people and destroying houses and property, had not only contributed to the extension of the period of distress, but had also called for renewal of relief operations, for which the colonial government was reluctant. The government, which had already spent money and deployed its administration for famine-relief, was reluctant to continue relief operations exclusively for the cyclones, especially at a time when famine-relief was about to be ended (especially for 1867, 1874, and 1897 cyclones). Therefore, relief for the cyclones, which occurred in 1867, 1874 and 1897, were merged with the famines, and the Cyclone Relief Funds were constituted under the supervision of the Famine Relief Funds. The question is that whether famine-relief had contradicted with cyclone relief or vice-versa? On the other hand, the cyclone of 1942 had provided a major blow to the official understanding that cyclonic impact was temporary. The causes of the Great Bengal famine of 1943 can be thus traced from the disastrous impact of the 1942 Midnapur cyclone. Hence, the present paper intends to critically evaluate the inter-relatedness of famines and cyclones in nineteenth and twentieth century Bengal.

2.15 PM – 3.45 PM: PARALLEL SESSIONS

Panel 3: Bengal Famine: Memories of Hunger

Chair: Dr Dhurjjati Sarma

Venue: Board Room

Deepawali Mitra (Jadavpur University)

“Remembering the 1943 Bengal Famine through Children’s Literature”

This article will attempt to understand how the 1943 Bengal Famine is memorialised in the short stories and editorials that were written during that time for the young readers. The famine of 1943, also known as ‘panchaser manvantar’ in reference to its Bengali year 1350, was the last major historical event of horrific deaths in undivided Bengal resulting from hunger and starvation. Drawing upon writings that were published in periodicals for children – Shishu Sathi and Mouchak– the article will focus on how these contributed to the shaping of the minds of young readers, who are thought to be powerless and helpless in this social and political world. By close reading of the short stories like Bhag-er Aalo, Lakshmi Narayan’s Puja, Ei Prithibir, Lesson Learnt By Adults From Kids, the article will show how these texts educated the young readers about the British imperialist policies,the suffering of the people and the divisions in the society, as well as inspired them to be transformative agents of change. Children’s literature is one of the ways that helps children and young readers to learn about emotions and develop an ethical and empathic understanding of society and its people. It was such a time that there was nothing much to expect from the adults, so the writers addressed the younger generation who are the inheritors of the future. This encouraged them to create literary memories and ensure that the children have a memory of the dark chapter in history, even though they may not have experienced it firsthand. The lessons in history will hopefully make them more socially responsible as adults and will ensure “never again” that there will be a repetition of such a disaster.

Shireen Sardar (Jadavpur University)

“Remembering Chiyattorer Monontor (Bengal Famine of 1769-70) – Politics of Colonial Crisis”

Bengal in the 1750s had a thriving agricultural economy that included widespread participation in rice cultivation and adequate rainfall. On one hand, Bengal’s sole focus on rice cultivation meant that when crops failed, it had no other crop to fall back on, On the other hand, reliance on rain meant that any shortfall would have a direct impact on the year’s harvest. Thus, the months of 1769-70 saw a disastrous crop failure, resulting in famine in Bengal, Orissa, and Bihar, which killed nearly one-third of the region’s population. However, severe weather constraints and a lack of rainfall cannot be held responsible exclusively for the Famine, which resulted in the deaths of up to 400,000 people. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to investigate the deeper causes of the Bengal famine of 1769-70. In doing so, this paper will attempt to demonstrate whether the Bengal Famine of 1769-70 was a man-made famine prompted by a colonial construct or a natural disaster induced by Bengal’s own economic scarcity, poor health conditions, or an absence of adequate transportation for food supply. Finally, the purpose of this paper is to remember one of colonial India’s earliest famines and its subsequent impact on colonial policies.

Srijita Biswas (IISER Bhopal)

“Writing Memory of Hunger: In Search of ‘Astonishing Smell of Rice”

The 1943 Bengal famine took place at a time when India was suffering from the aggressive consequences of World War II and Quit India agitations. Despite prolonged denial and lack of proper documentation poets, novelists, painters, and musicians of contemporary Bengal poignantly captured the violence and trauma of the tragedy. A lack of immediate documentation led many artists to take recourse to their memory for the purpose of realistic representation of the disaster. Practice of food rationing was institutionalised and violation of rationing provisions gave rise to hoarding and speculation in food items, introducing a new term- kalobajari or ‘black-marketing’ in Bangla vocabulary. Calcutta, the Second City of the Empire, was filled with cries of destitutes and phyan dao or ‘Give us little gruel’ became a historically haunting phrase thereafter. This paper would study the formation of a collective memory arising from scarcity of food during the fag end of British rule in India through analysis of select literary and cultural texts, highlighting role of memory and experiences of migration and movement during such a major fo crisis. The paper also aims to study the direct impact of the famine on the city of Calcutta along with consequent rise of a cuisine of scanty warped up by the famine, shaping identity from traces of memory and forms of resilience rooted in the overwhelming disaster.

Panel 4: Bengal Famine: History and Politics

Chair: Dr. Trina Nileena Banerjee

Venue: Conference Room

Subhasis Pan (Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University)

“Look Back to Hunger: The British Empire and the Bengal Famines in the Nineteenth Century India”

India witnessed more than twenty famines during the British Rule in India, though many of them remained unacknowledged by the British government. Out of these famines, Bengal suffered seven famines alone between 1770 and 1943; and four of them occurred during the last half of the nineteenth century (in 1866, 1873-74, 1892 and 1897). Whereas, there already exist a large corpus of data and a vast number of critiques on the great famines of 1770 (also known as Chhiyattorer Mannontwar, as it occurred in 1176 in the Bengali calendar year) and 1943 (that occurred during World War II), but the famines that occurred almost in subsequent decades in the nineteenth century Bengal had not gained attention to that extent.

In this paper I would try to examine the famines that had occurred in the nineteenth century Bengal and have been dealt with least attention. Again, the causes of these famines that led to the disastrous starvation of the people in Bengal would be analysed. The British policies of food and their myopic administrative exercises that failed utterly are under the scrutiny of this study, along with their callousness and indifferences to the subject people. However, the Scottish administrators who were the part of the British Empire had had a different take on the causes of the famines and policies thereof. The Scottish interventions in the study of the famines and the policies they advocated towards the remedial and preventive measures – as that of William Hunter, James Caird and others for the famines in Bengal and the neighbouring provinces create a space to form a critique on a distinctive Scottish attitude towards Bengal famines. The distinctive Scottish approaches and the Scottish principles with which they were imbibed would also be discussed in the course of this study.

Reeti Basu (Jawaharlal Nehru University)

“War, Famine and Foreign Soldiers”

During WWII, Bengal witnessed two events simultaneously, the coming of the foreign soldiers and the infamous famine of 1943. The paper explores how the Bengalis blamed the foreign soldiers for the famine and how the soldiers remembered the period. The public perception was that the government hoarded food for the soldiers while the native died of hunger. Moreover, the local society was morally degraded as impoverished women were sold to the soldiers. On the other hand, the soldiers were tired of hearing ‘fan dao’1 and the constant presence of the native beggars. While a few soldiers criticised the colonial government for negligence, others were shocked to see the number of dead bodies during the famine. The scholars had studied the causes and impact of the famine, but none had explored the soldier’s memory of the Bengal famine. Therefore, this paper will do a comparative study of civilian and soldier narratives of 1943’s Bengal famine. Both native and soldier’s testimonies confirmed that the famine only affected the local population; the foreign soldiers lived in opulence.

Dr. Ranu Roychoudhury (Ahmedabad University)

“Bearing Witness to Mid-Twentieth Century Hunger in India” (Online)

“I don’t think anyone will be able to ignore these images of starvation,” wrote Werner Bischof before beginning his work on “Hunger in Bihar,” commissioned by Life magazine. As the lead story in the Life on June 18, 1951, Bischof’s work augmented foreign aid for the newly independent India. However, this is counterintuitive to how the Bihar government opposed austerity measures imposed by the central government through Bihar Food Economy and Guest Control Order 1951. Indeed, Bischof did not document an officially declared famine but a moment in the long history of food shortage and hunger, interspersed with famines, that accompanied India’s transition from the colonial to the postcolonial. The juxtaposition of Bischof’s work with Sunil Janah’s photographs of the great Bengal Famine of 1943 and its continued effects across the subcontinent foregrounds the shared precarity of hunger, where famine as an administrative category takes a backseat. Consequently, visual arts provide a lens for this paper to complicate the critical events of famine per se by thinking about how documentary photographers witnessed starvation. This paper inquires the efficacy of photography as medium to bear witness to the quotidian and the everyday experiences of hunger in mid-twentieth century India.

4.00 PM – 5.30 PM: PARALLEL SESSIONS

Panel 5: The Famished Body: Visual Culture and Famine

Chair: Dr. Srimanjari

Venue: Board Room

Seng Ong (University of Cambridge)

“The Famine Pastoral: Colonial Famine and Western Visual Culture” (online)

This paper explores the visual culture of famine in China that was produced and consumed in Europe and America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. It argues that a focus on the mediatisation of famines sheds new light on the development of Western modes of visuality in China. The paper develops its argument in two sections. First, it traces the new modalities of visualisation which emerged in attempts by Western aid agencies to document the three epochal El Niño-Southern Oscillation related famines in late nineteenth-century China (1876–1878, 1896–1897, and 1899–1902). The seriousness of the famines was unprecedented, as was the intensity of foreign interest and intervention they provoked. Elucidating the grammar and protocols of looking which were utilised in these reports, I show how they drew on contemporary readings of famine whilst reformulating them in crucially divergent ways. The second section addresses the impact this mediatised disaster had on the subsequent development of Western photography and ethnography in China. Assessing the works of several important photographers and ethnographers, I show how the scopic regime of famine exerted a ramifying if unacknowledged force on how Chinese landscape and rural life was read and understood across the period.

Sumantra Baral (Jadavpur University)

“The Artist as Reporter: 1943 Bengal Famine and Inception of Visual Reportage in Colonial Bengal”

The proposed project will engage with visual reportage, a short lived print medium of aesthetic and literary-journalistic intervention of 1940s socio-cultural public sphere of colonial Bengal, Chittaprosad’s Hungry Bengal (1943), and Sudhir Khastagir’s Junput (1943) being central to the study. Visual Reportage, the act of producing ‘on spot’ witness accounts of visual and journalistic immediacy, implemented by ‘special artists’ (Paul Hogarth), started in Bengal with Chittaprosad at the time of 1943 Bengal Famine. Commissioned to capture Midnapur ravaged by famine, flood and disease, Junput appeared in the Nationalist Magazine Prabasi and Hungry Bengal in Communist periodicals People’s war and Janayuddha as illustrated travelogue reports, before published as a book. The contention here is to read these travelogue reports in the periodicals as promoters of news illustration in Bengal which introduced the era of socio-realist art, extremely different from the tradition of nationalist ‘High Art’. While Sachitra Masik Patrika or illustrated magazines in Bengal traditionally gave attention to art, 1943 Bengal famine introduced the genre of socio-realism that valued news illustration as serious art. The image-text symbiosis of the travelogue reports offered distinct representation of the famine which indicated the new role of artists as activists and reporters.

Attrita Goswami (University of Burdwan)

“The Famine in the Frame: Studying Visual Representations of the Famished Body in India and Ireland”