What music were people in Edinburgh making, creating, enjoying in the year 1841?

What part did this music play in their lives?

And how do we know?

This blog gathers material on the musical histories of Edinburgh in and around the year 1841. It builds on research conducted by first-year undergraduate students at the Reid School of Music as part of their course “Thinking About Music”. The final few weeks of this course take the form of a research module, during which students work in groups to investigate specific aspects of musical life in Edinburgh in and around the year 1841. Starting directly from primary sources such as concert listings, newspaper articles and sheet music, and under the guidance of teaching staff, they try to find out as much as they can about their sources and the musical life these sources document.

Why 1841?

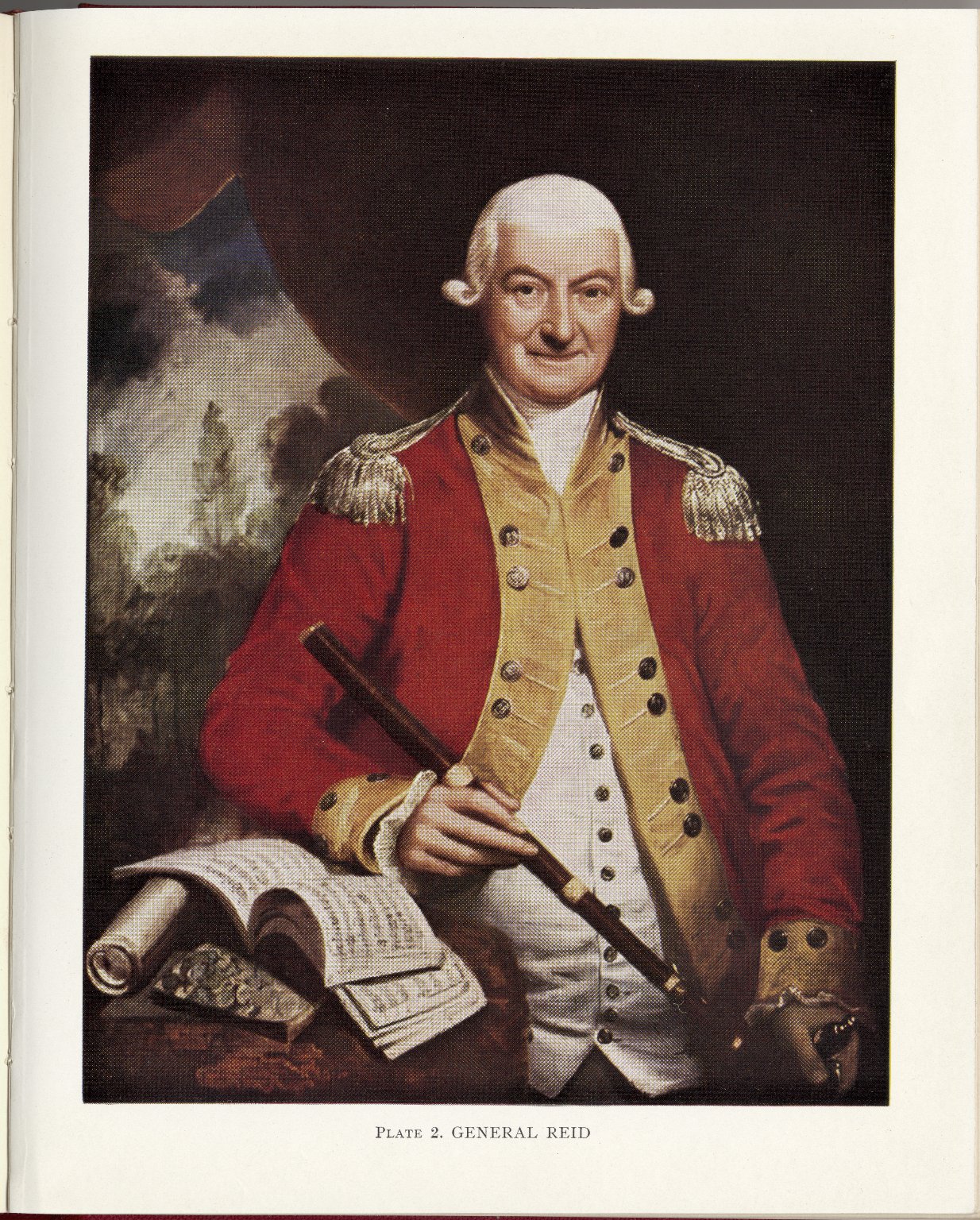

There are many reasons why the year 1841 was selected. It was the year of the first ever Reid Concert, a series set up as part of the legacy left to the University by General John Reid, and which still runs today. Reid’s legacy also led to the establishment of the post of Professor of Music at Edinburgh: the first incumbent, John Thomson, was appointed in 1839 but died in 1841; his successor, the renowned composer Henry Bishop, was also appointed in 1841. For us here at the Reid School of Music, then, the year 1841 is very appropriate; and other, external factors make it appealing as well:

- 1841 was the year of the first British census for which we have detailed historical records, which could help us find out more about the people who lived in Edinburgh at that time.

- Several important and relevant musical publications appeared in that year, including the final volume in George Thomson’s long running “select” collection of Scottish songs (a volume to which Henry Bishop contributed), and also the volume The Vocal Melodies of Scotland, edited by Finlay Dun together with John Thomson, who also wrote an introductory essay.

- And finally, musical visitors to Edinburgh that year included a certain Franz Liszt.

These are important starting points for us – but they are just that, starting points. These are the names that it’s easy to identify – names already well known, even if the details of their lives and works are in some cases much less well known today. What about the other lives, however? How much can we find out not just about these men but also their audiences, and the many other women, men and children who sang, played, listened, danced, discussed and invested time and money in music in this city of Edinburgh almost two centuries ago?

Academic standards

This page is built around research conducted by students at the very start of their academic careers. Original research is not normally conducted by students at this stage: often, the first really original research students undertake comes during final year dissertation projects, and it’s generally not until well into postgraduate studies that an emerging academic will see their research published. In our course “Thinking About Music” as well, conducting original research makes up only a very small part of the course. It’s an important part, however, because it underlines that universities are about the creation of knowledge, not just its recreation or replication.

This knowledge ultimately must serve the common good. There has been relatively little historical work done on musical life in Scotland in this period (or most periods, in fact). Through this blog, we hope to share this information with anyone who is interested, and thus contribute to building more knowledge in this field.

There is no expectation on students that they produce something that can be published here – and no limits set in terms of how they communicate their findings, except that anything published must conform to the standards of good academic practice: in other words, it must be original work, properly evidenced, and with credit given where it’s due. Checking that this is the case will be carried out by teaching staff.